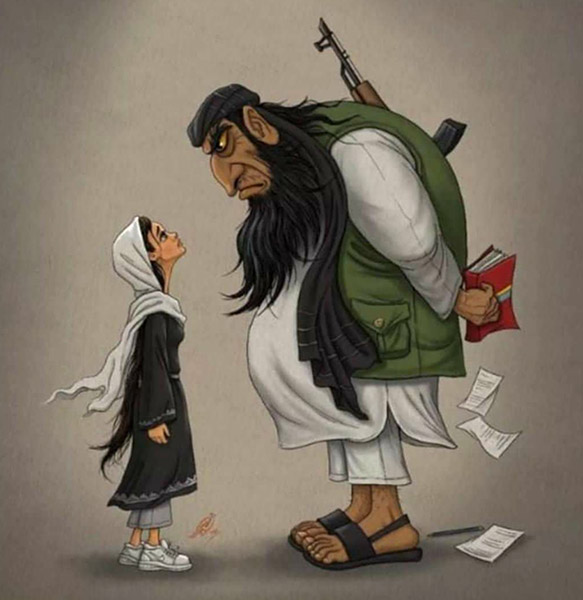

As Afghanistan’s new academic year gets underway with the ringing of school bells, nearly half of the country’s students are denied the right to education.

Despite the significance of Hamal 03 (March 23) as Afghanistan’s Education Day, the Taliban marked the start of the new school year on Hamal 01 (March 21) with a male-only ceremony at Amani High School in Kabul. No female teacher or student was allowed to attend the ceremony.

The Taliban cabinet’s ban on girls attending school from grades 6 to 12, which was imposed 548 days ago, remains in effect, closing not only schools but also universities and other educational institutions to girls.

The United Nations has recently stated that the Taliban’s ban on girls’ education oppresses women and the entire country, as it hinders Afghanistan’s development by preventing half of its workforce from participating.

Afghan Teachers, who are the driving force behind the country’s development, believe that blocking girls’ access to education has negative and destructive consequences both for the personal lives and education of girls and for the destiny of women and society as a whole.

As the school bell rings in Afghanistan, teachers are forced to confront the reality of gender-segregated classrooms where female students are prohibited from attending. With the start of the new school year, some teachers are speaking out about the psychological and emotional toll of teaching in this environment. They report feeling severely damaged by the ongoing denial of education to half of the country’s population, with some even questioning their own motivation to continue teaching in such conditions.

Aziza Karimi, a 30-year-old head teacher at a public school in Kabul, is speaking out against the Taliban’s ban on girls’ education. According to her, the ban “has no religious or legal basis, and is instead a political act.”

Karimi believes that this political treatment of women’s right to education will impact the entire country.

Shekiba, a 24-year-old teacher, is currently forced to stay at home due to the closure of schools for girls above the sixth grade.

“People’s indifference” to the closure of girls’ schools and “appeasement by the international community,” according to Shekiba, provided the Taliban group with an opportunity and motivation to use its decrees against women as a useful tool in the “slimy politics.”

“The Taliban’s stance on women’s rights and freedoms has been rooted in their religious beliefs, but they also utilize such issues as a means to further their political and military objectives,” she believes.

The exclusion of girls from middle and high school was just the start of a string of oppressive measures enforced upon women, which later infiltrated every aspect of their lives, Shekiba added. “The [Thaliban’s misogynistic] decrees encompassed universities, education centers, and public areas like stadiums and recreational centers, and even invaded the privacy of women’s homes and bodies, dictating their clothing choices and reproductive decisions”.

Aziza Karimi shares Shekiba’s views, adding “since the initial Taliban’s decrees against women went unchallenged by both the Afghan populace and the international community, it is now too late for any corrective measures.”

According to Masoma Jafari, a 30-year-old teacher at a private school in Kabul, “although the new school year has started, it is heartbreaking to see my students being relegated to menial tasks such as sewing and embroidery, instead of pursuing their studies and ambitious goals for the future. They have been forced to abandon their education and are now saddled with domestic chores such as washing and cooking.”

Jafari decried the situation as a grave injustice towards girls, stating that “the Taliban’s manipulation of our girls’ fate must come to an end. This is not just a matter concerning female students; this practice has the potential to obliterate an entire society’s future.”

Additionally, she expressed her sense of sadness and devastation, saying that “whenever I visit the school and observe the vacant and silent girls’ section, it fills me with despair and a sense of loss. The vibrant energy and eagerness that once filled the school premises have disappeared with the absence of girls.”

Gender discrimination in Afghanistan has a profound and long-lasting impact on girls, according to the teachers. They believe that girls are acutely aware of the unequal treatment they receive compared to their brothers, who are free to pursue their academic and career goals without hindrance. The disparity in treatment leaves a heavy and irreparable impact on girls, reinforcing outdated gender roles. Unfortunately, the lack of action against gender discrimination is a problem at both the macro and micro levels. Just as people failed to stand up against Taliban oppression, families are also failing to support their daughters.

“My uncle’s three daughters, who were previously students in the seventh, ninth, and eleventh grades, now weave carpets to provide food and meet expenses for the family,” Masoma told Nimrokh.

However, physical labor is not the only concern for young girls, as forced and premature marriage poses a more significant threat to their future.

“A 15-year-old student of mine once confided in me that her father was planning to force her into marriage,” Aziz Karimi told Nimrokh. “Despite my prolonged efforts to persuade her father otherwise, he remained steadfast in his decision. Recently, she was smuggled to Iran via Nimroz to be handed to her future husband.”

According to the teachers, their students frequently come to school with grievances about the humiliating conditions of being confined to their homes. However, “we are all unable to take any action, being left in tears.”

This perplexity and frustration have led to a loss of drive among the schoolteachers. According to Karimi, “Observing that half of our school’s girls’ sessions are shut down leaves me with little incentive to persevere.”

As per these educators, the sole means to safeguard girls’ entitlement to education is by combating policies that promote misogyny.

From their point of view, both the Taliban’s limitations and societal apathy towards those limitations are promoting political and cultural misogyny. Overcoming this predicament, they argue, requires the collective support of the global community and the people of Afghanistan for those students who yearn to attend school, yet are unjustly barred from doing so.

These educators stress the importance of working on initiatives that allow girls access to education and universities, rather than investing in programs and projects that solely focus on sewing and beekeeping skills for women. They urge society to refrain from expressing regret and coercing their daughters into marriage or strenuous labor and instead stand in solidarity with them.