By Peter Maass

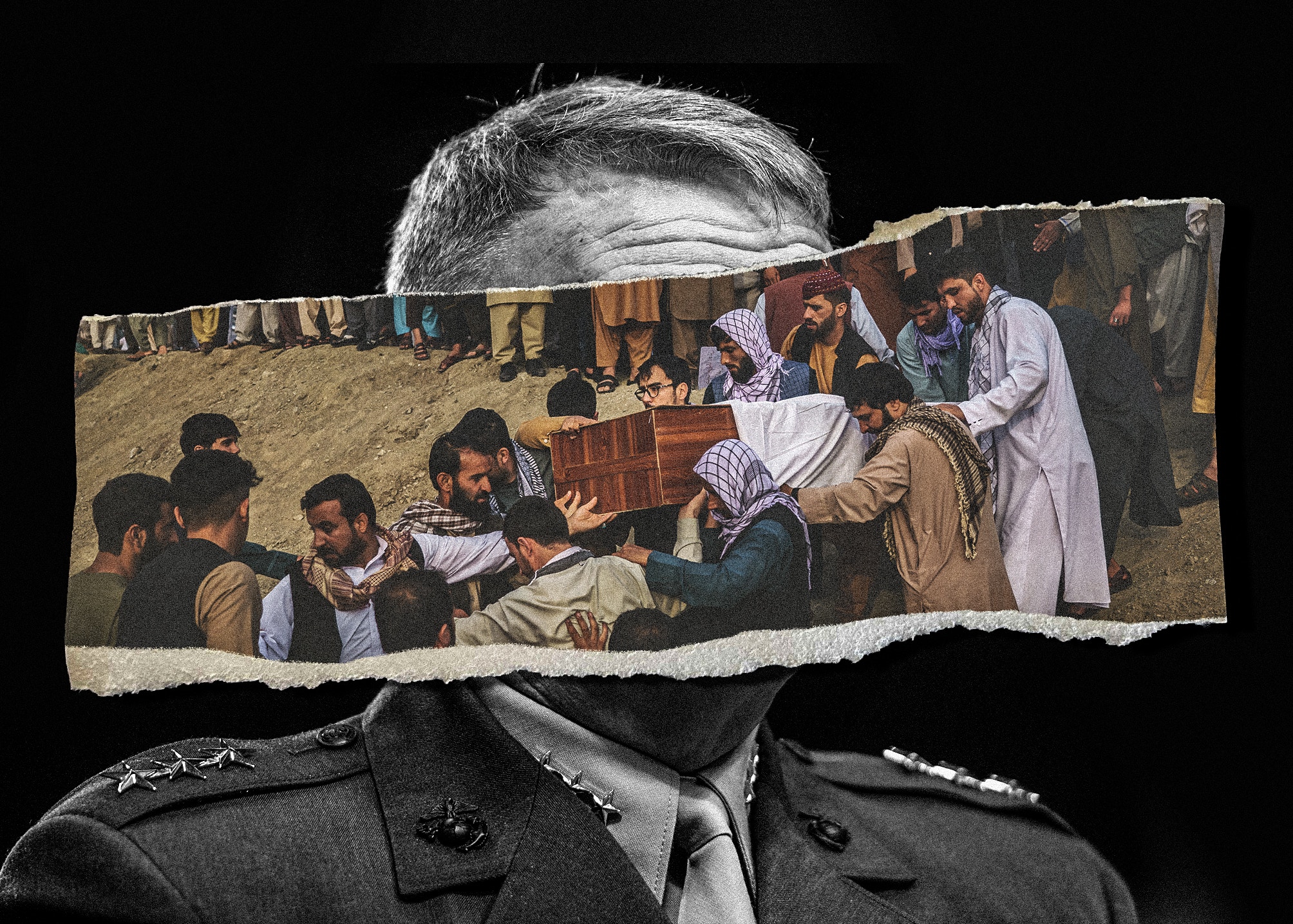

Relatives carry caskets at a mass funeral for members of a family killed in a U.S. drone strike, in Kabul on Aug. 30, 2021

IF YOU ARE waiting for an American general to resign or be fired over the drone strike that killed seven children and three men in Kabul last month, you will likely experience the meaning of infinity.

You might think that the Pentagon would be scrambling to find a general to take the fall for what can no longer be denied: that the U.S. military killed 10 Afghans on August 29, called it a “righteous strike” against terrorists, and then had to admit the truth after journalists found out what happened. But don’t bet your bitcoin on it. The military is already saying that standard targeting protocols were followed for the Kabul attack; the problem was a faulty assumption or two, we meant well, next time we’ll do better.

The generals are in a corner. If they admit that the Kabul massacre is resignation-worthy — and in a healthy society, a massacre would be — they would have to admit that resignations should have occurred after the multitude of U.S. bombings and attacks in the past 20 years that killed large numbers of civilians doing nothing more sinister than attending a wedding party, seeking care at a hospital, or picking pine nuts. The Kabul bombing was an outlier only in the amount of attention it received; the killing of civilians has proven to be a feature rather than a bug of the 9/11 wars.

The generals who have overseen two decades of carnage in Afghanistan and Iraq are inept at winning wars, but they possess one skill in abundance: a knack for avoiding career consequences for their too-many-to-count errors. The generals, as well as the politicians who approve ever-rising military budgets, have managed to lull the country to sleep with a euphemistic lullaby about what they want us to limply understand as an infrequent phenomenon of “collateral damage.”

The lack of resignations, whether forced or voluntary, attests to a character trait that is not traditionally attached to U.S. generals but should be: cowardice.

Moral Cowardice

Let’s focus on moral cowardice. Since 2001, not a single general has had the courage to say, “Enough, I will not be part of this killing and deception any longer, it is wrong and harmful to all, here are my stars.” Again and again, the generals have tolerated, excused, and lied about the slaughter of civilians in the 9/11 wars — at least several hundred thousand noncombatants have been killed in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the number is probably far higher. What happened in Kabul last month is a case study of all those pathologies of denial poured into one tragedy.

Courage is required to admit that you were dead wrong, to take an unpopular stand against your brethren, to cast shame on them, to bring on their disapproval. Courage is also necessary to sustain an objector in the aftermath of breaking away. Though a dissenting general would retire with a generous pension, he could forget about landing the lucrative corporate gigs, usually with military contractors, that shower millions of dollars on former commanders who lend their prestige to forever warfare.

In other words, it doesn’t require a ridiculous amount of courage for a general to do the right thing.

We have to look elsewhere, far below the military’s upper echelons, to find the courage that ending 20 years of unlawful warfare requires. Look, for example, to Daniel Hale, who worked on the intelligence side of drone warfare for the Air Force and came to be repulsed by it. In 2015, Hale leaked classified military documents that revealed the underside of the U.S. drone program and in particular the weaknesses of its targeting protocols and its tendency to kill people who were not the intended targets. The Intercept published classified documents about problems in the U.S. drone program in an eight-part series in late 2015.

“With drone warfare, sometimes nine out of 10 people killed are innocent,” Hale has explained. “You have to kill part of your conscience to do your job. … I stole something that was never mine to take — precious human life. I couldn’t keep living in a world in which people pretend that things weren’t happening that were.”

Today, Hale is not pulling down six figures a year as a board member of Raytheon Technologies or Lockheed Martin. He is serving a 45-month prison sentence for violating the Espionage Act.

Fire the Generals

Of course, getting rid of the senior leadership of the armed forces would be an incredibly radical move, but Andrew Bacevich has put forward a plan to do just that.

Bacevich is a retired Army colonel who in recent decades emerged as one of the most prominent intellectual critics of American foreign and military policy. On the 20th anniversary of 9/11, he published a lightly noticed article proposing a wholesale clearance of the nation’s military leadership due to their losing streak. Its winking title was “A Modest Proposal: Fire All of the Post 9/11 Generals” — but Bacevich stressed that his piece was not a Swiftian satire.

U.S drone strike in Kabul killed 10 civilians mostly children.

“Allow me to suggest … a purge,” he wrote. “Oblige all active duty three- and four-star generals (and admirals) to retire forthwith. Rebuild the ranks of the senior officer corps with members of a younger generation willing and able to acknowledge the shortcomings of recent American military leadership at the top.”

To find the replacements, Bacevich suggested that the secretary of defense — though not the current one, Lloyd Austin, who was a four-star general until recently — personally interview one- and two-star generals who show promise and ask this one question: “On a scale of one-to-ten, where one is lousy, ten excellent, and five mediocre, how would you rate U.S. military performance over the past 20 years?” Generals who give a rating of five or below would proceed to the next round, consisting of writing an essay in two hours that answers the question, “What is the problem and how do we fix it?”

Bacevich concluded, “Those essays should provide the basis for selecting and assigning the next generation of senior leaders.”

There’s no need to wonder whether the next generation would be better than the present one, because Bacevich’s plan is not going to be adopted; the generals don’t want it, and the politicians don’t want it. We’re stuck with a cadre of military leaders who lack the courage to admit the dishonor of killing civilians.