Arab News, September 11, 2020

Queen Soraya of Afghanistan: A woman ahead of her time

Soraya Tarzi gave her compatriots a glimpse of a gender-equal future that has yet to be fully realized

By Jonathan Gornall and Sayed Salahuddin

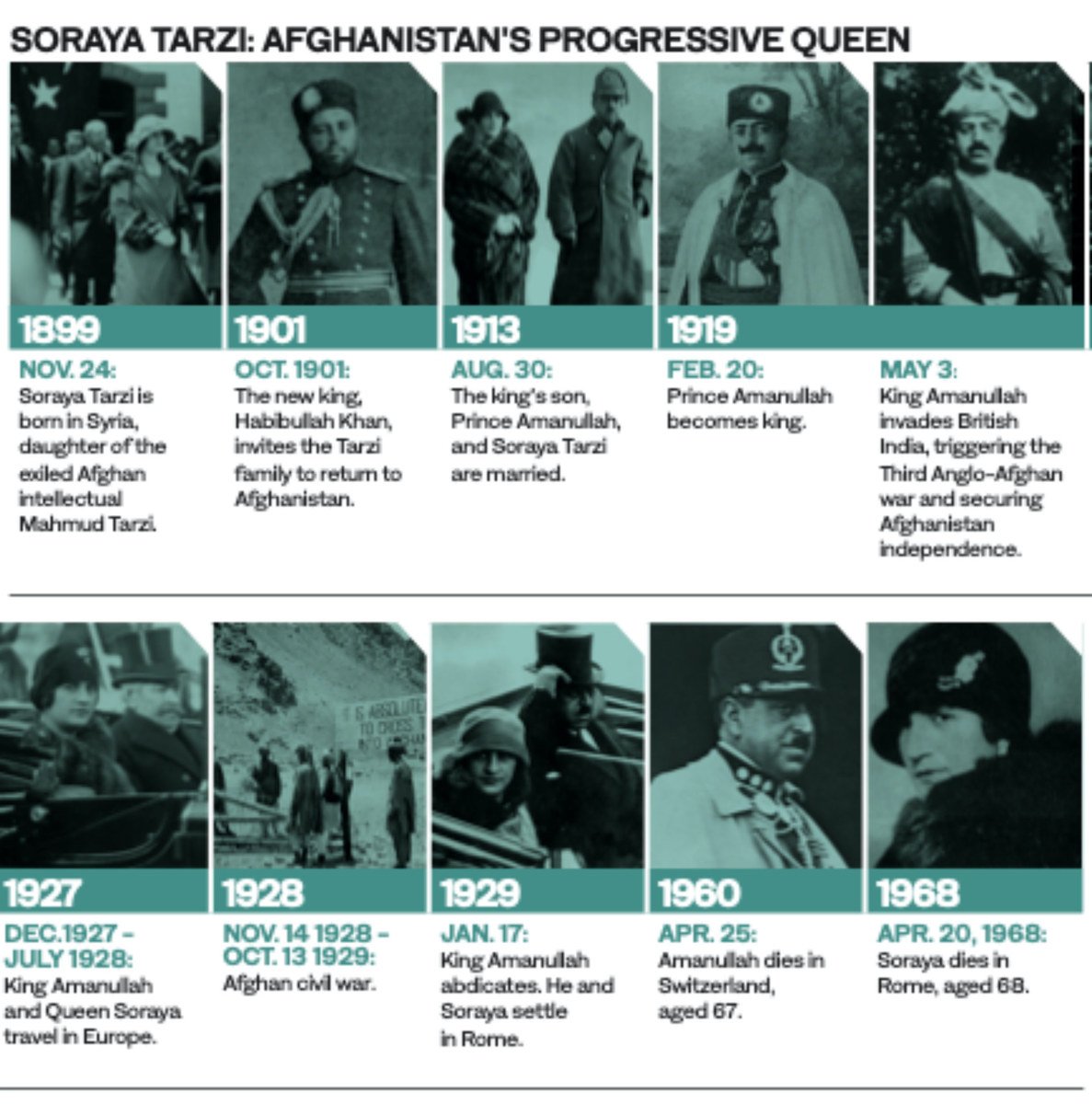

LONDON/KABUL: Born in exile, she died in exile. But during the 10 controversial years she spent as queen of Afghanistan, Soraya Tarzi gave the women of her country a tantalizing glimpse of an emancipated future which, a century on, has yet to be fully realized.

Barely remembered in the West, where she was once greeted by vast crowds during a triumphant tour of European capitals in 1927-28 with her husband King Amanullah Khan, earlier this year Queen Soraya was celebrated by Time magazine, in a series honoring the forgotten female pioneers of world history.

For 72 years, Time had named a “Man of the Year.” In 1999 it changed this to “Person of the Year” but, to recognize the women it had overlooked in the past, in March Time created 89 new online covers spotlighting “influential women who were often overshadowed”. The choice for 1927 was Afghanistan’s progressive queen, who was driven into permanent exile in 1929.

“Soraya was the first Afghan lady and queen who began to promote women, educate them and try to give them their rights,” said women’s rights activist and MP Shinkai Karokhail, Afghanistan’s former ambassador to Canada.

The queen “began a great revolution and managed to implement it through the king. She appeared in public and travelled extensively to inform women about their rights and that they needed to acquire education.”

For her time, “she was unique – a very strong and exceptional woman.”

In 1926, on the seventh anniversary of Afghanistan’s independence, Soraya delivered a characteristically provocative and inspiring speech.

Independence, she said, belonged “to all of us … Do you think that our nation from the outset needs only men to serve it? Women should also take their part as women did in the early years of our nation and Islam … we should all attempt to acquire as much knowledge as possible.”

Following their European tour, the king and queen returned to Afghanistan in 1928 determined to modernize their country. But, says Zubair Shafiqi, a Kabul-based journalist and political analyst, they moved too fast.

“She and the king began to bring changes, reforms and freedoms after their joint trip to Europe, where both were influenced by what was going on there,” he said.

“But they had not comprehended the backwardness of Afghanistan, a traditional and conservative society. They both acted hastily, which provoked people and led ultimately to revolt.”

After a year-long civil war, in 1929 King Amanullah abdicated and fled with his queen to British India.

The king is remembered as a great reformer, but Soraya was the driving force behind his agenda. Born on Nov. 24, 1899, in Damascus, where her family had settled after being exiled from Afghanistan in 1881 following the rise to power of Abdur Rahman Khan, she inherited her progressive thinking from her father, Mahmud Tarzi.

Queen Soraya ans King Amanullah during their visit to Paris inspect a military guard of honor

Tarzi was an Afghan intellectual whose liberal and nationalist ideology sat uneasily with Khan, who had been installed as ruler by the British in 1880 following the defeat of his predecessor in the Second Anglo-Afghan War.

As an exile, Tarzi’s travels in Europe and life in Turkey had broadened his horizons and he was determined to do the same for his country. His chance came in 1901 with the death of Khan and the accession to the throne of his eldest son, Habibullah Khan, who invited Tarzi and other exiled intellectuals to return to Afghanistan.

As a member of the government, Tarzi embarked on an ambitious program of modernization. His daughter Soraya, meanwhile, met and fell in love with Amanullah Khan, the king’s son, and on Aug. 30 1913, the two were married.

On Feb. 20 1919, Habibullah Khan was assassinated. After a brief family struggle Prince Amanullah claimed the throne. Soraya was now queen and her reforming father, Mahmud Tarzi, became foreign minister.

Events moved quickly. On May 3, 1919, King Amanullah, determined to pursue the nationalist policies advocated by Tarzi, took the audacious step of invading British India.

The Third Anglo-Afghan War, better known in Afghanistan as the War of Independence, was all over by August. Britain, drained of men and resources by the First World War, agreed to an armistice and at Kabul on November 22 1921, Tarzi and Henry Dobbs, chief of the British mission, signed a treaty committing the two nations to “respect each with regard to the other all rights of internal and external independence.”

Afghanistan had finally thrown off the shackles of British imperialism. Tarzi set up embassies in a series of European capitals and, with the enthusiastic support of the king and queen, pressed on with modernizing his country.

As Time’s tribute in March recalled, “in the face of opposition,” the king and queen “campaigned against polygamy and the veil, and practiced what they preached.” The king rejected the traditions of taking multiple wives and maintaining a harem, while his queen, “a fierce believer in women’s rights and education … was known for tearing off her veil in public.”

The first primary school for girls, Masturat School, was opened in Kabul in 1921 under the patronage of Queen Soraya, who in 1926 was named minister of education. More schools followed, and in 1928 15 students from Masturat Middle School, all daughters of prominent Kabul families, were sent to Turkey to further their education.

It was a provocative move.

In present-day Afghanistan, between 3.2 and 3.7 million children aged 7 to 15, 60 percent of them girls, remain out of school, while drop-out rates are high

“Sending young, unmarried girls out of the country,” wrote the academic Shireen Khan Burki in the 2011 book of essays “Land of the Unconquerable: The Lives of Contemporary Afghan Women,” “was regarded with alarm in many quarters as yet another sign that the state, in its efforts to Westernize, was willing to push against social and cultural norms.”

The king’s gender policies “were completely divorced from the social realities of his extremely conservative, primarily tribal, and geographically remote country.”

The final straw for many came in December 1927, when the king and queen embarked on an expensive six-month tour of European capitals.

In England the couple were met at Dover by the Prince of Wales and ferried by royal train to London, where they were greeted at Victoria station by King George and Queen Mary. The royal party then travelled in open horse-drawn carriages to Buckingham Palace through streets thronged with cheering crowds.

Their reception in other European capitals – and in Moscow, a pointedly political stop for the King and Queen of a country seen by the British as a buffer against Soviet ambitions in the region — was equally rapturous.

APR,20,1968 Soraya died in Rome, aged 68

But upon their return to Afghanistan in July 1928 it quickly became clear that the great European tour had been a terrible mistake. “In a matter of months the progress that Soraya had made was relinquished,” said Mariam Wardak, an analyst and advocate for gender inclusion in Afghanistan who co-founded Her Afghanistan, an organization dedicated to the advancement of young Afghan women.

As the king tried to appease his critics, “secular schools, including girls schools, were closed, family laws banning polygamy and granting women the right to divorce were repealed, secular courts were disbanded for sharia courts and much more.”

It was in vain. By November 1928 Afghanistan was engulfed by a civil war, with opposition forces led by Habibullah Kalakani, the so-called bandit king. In January 1929 Amanullah abdicated and fled the country.

Kalakani held on to power for just 10 months. On Oct. 13 1929, he was overthrown and executed by Nadir Shah who, with the help of the British, installed himself as king.

To this day many in Afghanistan believe that the British government had a hand in the overthrow of Amanullah and that, to sabotage his reign, it mounted a covert campaign of fake news against his wife.

“While accompanying King Amanullah on his overseas trips, she represented the young modernity of Afghanistan and the new era both wanted to broaden and consolidate at home,” said historian Habibullah Rafi. “But our evil enemy, the British empire at the time, having failed in Afghanistan and in order to avenge its defeat, began spreading false information about her goals as it wanted to block progress here.”

The British, he says, distributed doctored photographs showing the queen abroad with bare legs – a shocking sight for many back home. Britain, said Rafi, “could not afford to see a free and prosperous Afghanistan, as India, which was under its firm occupation, would have been inspired by our freedom and progress and would have also revolted. That is why Britain did all it could to undermine the then government, and especially the queen.”

Whether or not the British did mount a dirty-tricks campaign against Amanullah and his wife, once-secret cabinet papers seen by Arab News reveal that Britain enthusiastically backed Mohammed Nadir Shah, Amanullah’s successor as king.

Britain’s main concern at the time was the protection of India, the jewel in the empire’s crown, which it felt was threatened by Amanullah’s increasingly close relationship with the Soviet Union. To the alarm of the British, in May 1921 Amanullah had signed a treaty of friendship with the Soviets.

In 1932 Amanullah’s successor asked the British for assurances of help in the event of a feared Soviet invasion, and one paragraph in a telegram sent to London by the British government of India on Sept. 10, 1932, confirms the empire’s meddling in Afghanistan’s internal affairs.

The Afghan government, wrote the anonymous author, was “aware that their internal position is very unstable owing to pro-Amanullah propaganda [and] the assistance received from us by Nadir in securing throne.”

In exile King Amanullah and Queen Soraya travelled to Italy, where they spent the rest of their days in Rome. Amanullah died in April 1960. His wife lived for another eight years. After her death at the age of 68 in April 1968 her coffin was given a miltary escort to Rome airport and in Afghanistan she received a state funeral.

Today, the former king and queen lie together with Emir Habibullah in the family’s mausoleum in the Amir Shaheed gardens in Jalalabad.

Oct. 11 is International Day of the Girl Child, held to raise awareness of the obstacles that girls all over the world face. This year, Education Cannot Wait, the organization established at the World Humanitarian Summit in 2016, is highlighting those obstacles by focusing on the plight of girls in Afghanistan.

“More than three decades of conflict have devastated Afghanistan’s education system and completing primary school remains a distant dream for many children, especially in rural areas,” according to ECW.

It says that in Afghanistan between 3.2 and 3.7 million children aged 7 to 15, 60 percent of them girls, remain out of school, while drop-out rates are high.

Ninety years after her attempt to liberate Afghan girls and women ended in revolt and a return to a time-honored system of repression, Soraya would be saddened to see how little progress has been made in her country since then.

“I admire Queen Soraya’s efforts,” said Wardak, the advocate for gender inclusion in Afghanistan, “but I believe she could have been more effective if she had adopted a more subtle approach on how to advance women's rights.

“Today, we struggle with many rights of women to be practised, underage marriage still exists and people still give and receive dowry.”

Nevertheless, Wardak said, “I believe the vision of Queen Soraya still lives in many young leading women today and will stand strong in generations to come, if we continue to educate our society. Education is key.”

Characters Count: 14404