A new law designed to regulate Afghanistan’s nascent mining sector could increase corruption, lead to forced displacements and even allow armed groups to take control of the sector, transparency groups have warned.

The law, passed by parliament earlier this month, is likely to lead to the signing of several key deals to extract the country’s newfound minerals - estimated to be worth as much as US$3 trillion.

Yet the transparency organization Global Witness warned that the law “does not include basic safeguards against corruption and conflict”, a view supported by a key Afghan NGO. Government officials deny the claim, saying that further protections are to be written in later.

A question of law

Afghanistan’s discovery of huge reserves of key minerals in recent years has raised hopes of a bounty of deals that could potentially help the country’s economy grow, and stabilize the country, following the pullout of US troops at the end of 2014.

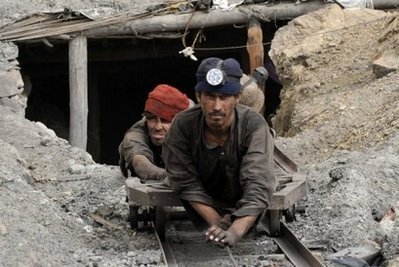

Afghan miners. (Photo: Gold and Mining Market Wrap)

Yet the bids have been delayed by what were perceived as an unfriendly legal framework for business. Sayed Hashemi, legal director at the Afghan Ministry of Mines and Petroleum, said a previous law signed in 2010 was seen as too tough on companies as it did not allow them to turn exploration licenses into exploitation. “No investor was interested to come into Afghanistan,” he told IRIN. As such, the ministry designed a new law to cover the mining industry, with Hashemi saying they wanted to make investing easier.

Yet critics charge that the new law is open to abuse and actually worse than its 2010 counterpart. Stephen Carter, Afghanistan campaign leader at Global Witness, said Afghanistan’s law falls far short of many of these standards. He said anti-corruption measures, protection for those affected by the mining, and basic safeguards for the allocation of licenses were missing from the law.

Javed Noorani, a senior researcher at Integrity Watch Afghanistan, argued that the law failed to protect the sector from armed groups. Without new protections, he said, the already fierce competition over minerals was likely to increase conflict.

“[Contracts] will go to the powerful mafia, insurgent groups operating in provinces. The sector will be completely captured. The bidding process will be as non-transparent as possible,” he said. “We may relapse into a conflict over natural resources. The revenue will go to pockets and that will take a flight out of the country.”

A lack of transparency

The country already has chronically high levels of corruption. Afghanistan scored 155th out of 157 countries in Transparency International’s 2013 Corruption Perception Index, while in 2010 the US temporarily suspended aid after allegations that billions of dollars were being stolen.

Dealing with such issues legally can be a challenge. Jenik Radon, Adjunct Professor at Columbia University, explained that writing effective and sound extractive laws to protect a nation and its citizens is extremely difficult as a significant number of issues need to be considered, balanced and integrated. Among theses are protecting the environment, rights of and compensation for those displaced and impacted, transparent payments and sufficiently strong enforcement of laws and contracts of companies that do not comply with their obligations, or as a citizen would understand, keep their promises. “It is incredibly difficult to draft a good, effective and balanced law as you have to take a multitude of issues into account and all the while keeping in mind that you, as a drafter, have a responsibility to protect the public interest, the common good, the nation” he said.

One of the key criticisms of the law is the lack of a specific clause demanding that the ownership of all companies involved in deals be made public. Carter said the decision not to specify it in the law was “deeply worrying.”

Radon explained that such clauses were increasingly standard practice across the globe as a way of protecting against corruption. In particular, they sought to avoid money disappearing to the Cayman Islands and other tax havens without record. Such clauses also help prevent armed groups from directly or indirectly profiting from the sector, he added. “It is a question of knowing who you are dealing with,” he said.

Hashemi said the government was trying to balance a desire for transparency with safety. Releasing all the information about those involved in deals would put them at risk of kidnapping, he said.

“It is Afghanistan. It is not Paris or London. We have to be worried. Security is the first thing otherwise you cannot bring industries into this country,” he said.

Hashemi gave the example that in recent years bank insiders had been alleged to have provided information leading to kidnapping. “If you give all the information available to the public and to the people, that is when corruption is going to happen, that is why crime is going to happen,” he said. “If it is proprietary information or it is dangerous to the security, that cannot be disclosed. The rest of the information is absolutely public and available.”

Asked who would decide whether revealing details endangered individuals, Hashemi said it would be a decision made on a case-by-case basis by an inter-ministerial committee.

Compensation for displacement

Another area of concern is over those communities that may be forced to move for the development. Radon, who has advised on oil and minerals deals in over a dozen countries on behalf of states and their governments, said that one of the key issues in many emerging or developed countries was reaching a fair compensation for those that lose their houses or otherwise impacted.

“Often you don’t have a reliable registry of who lives on or owns certain property. You therefore have to think in non-traditional terms concerning land. Who are the people living on the land and how long have they been there? What rights as dwellers do they have. ” he said. “ While compensation needs to be paid to people who actual own property as well as those living on it, you also ought compensate those whose property or lives is indirectly affected by the noise or other inconveniences that extractive development brings,” he added.

In Afghanistan it appears that such agreements will be much needed. On top of the new facilities that will be built, the government has promised to build a new network of railways to support the mining industry, potentially displacing tens of thousands of people.

Carter of Global Witness said the Afghan law only sets the conditions for compensation of those parties that own the land. In Afghanistan, he said, many communities had long roots in areas but do not own the land.

In a report on the law published late last year, Global Witness found that while the law offered provisions for compensation, “community members are unlikely to be parties to the contract… and can potentially be excluded from attending hearings or submitting information.”

Hashemi added that while the law had been drafted, many of the specific regulations were still being debated and would be confirmed later. He denied claims that civil society groups had not been sufficiently consulted and stressed that they were still seeking to improve the law in the coming months. “Many of the criticisms from Global Witness and others can be covered within the regulations,” he said.