By Lance Richardson

A few years ago, award-winning journalist and poet Eliza Griswold learned the story of Zarmina, a young girl in Afghanistan who had regularly phoned a radio hotline for women who wanted to share poems called “landays.” Landays are couplets expressing laments, jokes, and frustrations; they are forbidden to many Afghan women because they imply dishonor and free will. When Zarmina was discovered writing them, her brothers beat her badly, and she protested by setting herself on fire. She later died in a Kandahar hospital.

Griswold teamed up with war photographer Seamus Murphy and reported the story of Zarmina for the New York Times Magazine in 2012. After the article was published, their work together bloomed into a much larger collaboration about Afghan women, which resulted in a a photographic and poetry compilation called I Am the Beggar of the World: Landays From Contemporary Afghanistan.

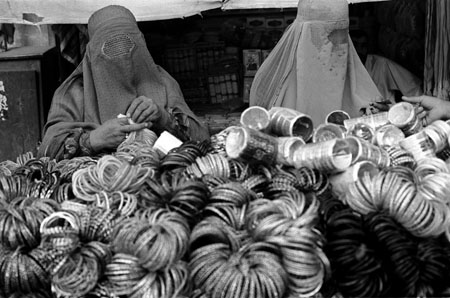

Women shopping for bangles at a bazaar, Kandahar, August 2004. (Photo: Seamus Murphy/VII)

Griswold and Murphy recognized that landays were being used as a means of self-expression and education at a time when opportunities for women were rapidly diminishing. “We came up with the idea of using contemporary landays to look at not only Afghan life, but also the impact of the last decade of war on the lives Afghan women, especially at this very delicate moment when the international pullout could leave those voices most vulnerable,” Griswold said.

May God destroy the Taliban and end their wars.

They’ve made Afghan women into widows and whores.

Collecting material was a painstaking process. Griswold ventured into refugee camps and private homes looking for poetry. Murphy, for his part, dedicated two trips to Afghanistan to capturing photographs of everyday life; he later augmented these with previously unused images drawn from a personal archive covering two decades of war reporting.

Your eyes aren’t eyes. They’re bees.

I can find no cure for their sting.

The idea was not to “illustrate” Afghan life in a straightforward sense. Photographs were never intended to correspond to poems directly. “What we looked for was how images and words could enlarge one another through a relationship that wasn’t necessarily a direct one,” Griswold said. Murphy explained that this meant an obvious choice—a drone photograph for a landay mentioning a drone, for example—was often passed over for something more associative. “Because you’re talking about two different things, you then end up with a third thing,” he said.

I’ll kiss you in the pomegranate garden. Hush!

People will think there’s a goat in the underbrush.

During the editing stage, Murphy also shied away from selecting photographs that showed female faces. Taking pictures of women has always been a fraught endeavor in Afghanistan, and even photographing burqas has gotten Murphy into trouble. But the project itself called for concealment. “One of the virtues of landays, and how these women can continue to produce them, is [because] they’re anonymous,” Murphy explained. “So it’s kind of against the spirit of what they’re doing to be chasing faces. The deal is that it’s the inner world of women.”

How much simpler can love be?

Let’s get engaged. Text me.

Griswold described the landays as a window into the psyche, and one that “unsettles” stereotypes of passive Afghan women. Her favorite landay, for example, is “so brutal, and so funny, and so light, and almost falsely naïve”:

When sisters sit together, the always praise their brothers.

When brothers sit together, they sell their sisters to others.

“What is clear [after reading the poems] is that we have no idea what’s going on beneath those iconic burcas,” Griswold said. Murphy added that “it’s about their lives,” and his photographs try to get as close as possible to the truth of that.