By Rustam Qobil

In many areas of Afghanistan it is the warlords who hold sway - not the central government or the Taliban. They are able to exploit villagers with impunity using the threat, or the reality, of violence.

In rural Takhar province, in the remote north-east of Afghanistan, time seems to have stopped in the 19th Century - bumpy roads, mud-built houses, lawless villages and no sign of the Kabul government.

Here, armed commanders and their guns are in charge. Their word is the law.

"Local armed commanders forced three of my elder brothers to fight for them against the insurgents," 26-year-old Najbulla tells me. "They were all killed in wars."

Najbulla - not his real name - speaks quietly because he is scared of being overheard, so we move to the back room of his friend's shop.

"Now they want me to be their soldier, too. But I need to look after my old parents and orphaned nephews, so I refused," he says.

"Ever since, they have been threatening to kill me and grab our land."

Najbullah doesn't know what to do. Moving somewhere else is not an option. He's a poor farmer, with a big family to look after.

He says there is no-one who can help him, either. Officials and the police are either scared of the armed warlords or working for them.

Both the Soviets and the Taliban struggled to gain control of this part of Afghanistan and its "mujahideen warlords", who today rule unchallenged.

In a region with few prospects, many young men end up fighting for the warlords.

In some places they impose taxes on local traders. Some have become government officials. Some run anti-Taliban militia groups, called Arbaki, which are supported by the government and international forces.

And many ordinary Afghan people are terrified of them. They say the commanders extort money and food, grab land, assault people - and sometimes kill.

Takhar province is situated on the southern banks of the Amudarya - the biggest river in Central Asia. Its tributaries should be able to provide enough water for all the region's agriculture - but, oddly, many farmers struggle to irrigate their crops.

In one district, Khojaye Ghor, the irrigation canals have dried up completely and crops are failing - hundreds of families have had to abandon their homes in search of water.

The explanation lies upstream.

"Some powerful and armed people... diverted our river to power their hydro-electric generators," one local farmer, Muhammad Sharif, complains.

One of them is Mr Aghagul Qataghany, he says - a former mujahideen commander, now mayor of Taloqan, the capital of Takhar province.

When I meet him in his office, he denies the allegation.

"Show me that person and I'm ready to challenge him in court. I don't have any hydro-power generator," he tells me.

But others back up the farmer's story.

Najibulla Khaliqyar, the head of the Provincial Council of Takhar, agrees Qataghany and others are diverting rivers for power.

"We just can't do anything against them because the government is weak and these commanders do actually represent the government here," he says.

"They are powerful people with good connections."

The might of the warlords goes back at least to 1979, when the country was invaded by the Soviet Union, and weapons started flowing into the region.

"A local commander grabbed my land 30 years ago," says an old man in his 80s, who I meet in Takhar.

"Now his son uses my land and despite having all the necessary documents I can't get it back. They beat me up and tried to kill my son. He had to flee to Iran."

He shows me dozens of documents. Some date back to the Soviet occupation, some are brand new. But they are just useless pieces of paper, powerless against the rule of the gun. Once a landowner, this man is now penniless and homeless.

Heather Barr, of Human Rights Watch in Kabul, says it's the same in many rural areas across the country.

"The government and international community have empowered these commanders and their groups by giving them more control in rural areas and turning them into anti-Taliban militia forces, or local police," explains Heather Barr.

"The country is being left to these people."

Critics say the national government is turning a blind eye to these problems.

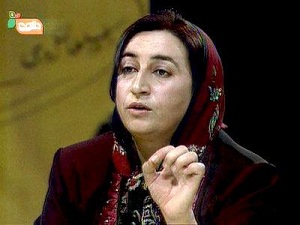

"Many warlords or armed commanders are in the government and they are very powerful and in provinces it's their men who are in control," says Bilqis Roshan, a senator from Farah province.

"I know cases of rape and murder but those who committed these crimes are still at large simply because they are powerful commanders or have links to them."

Government officials admit the problem exists - but they say action is being taken to deal with it.

"We do have some problems with local police and Arbaki forces," says Siddiq Siddiqi, spokesman for Afghanistan's Ministry of Internal Affairs in Kabul. "But whoever breaks the law, they will be punished."

However, it seems ordinary people cannot get justice, even in the Afghan capital itself.

"A local armed commander killed my father and grabbed our land," says a woman I meet in the city.

"When he wanted to marry my teenage daughter by force I abandoned everything and fled to Kabul together with my children."

She cannot now go back to her village or claim her property back.

"He is a former mujahideen and a powerful man and has connections everywhere, so there is no point in complaining against him. It will only worsen my situation," she says.

She has been in hiding in Kabul for the last five years. All her young children have to work to supplement what she earns as a cook.

Nato is planning to withdraw most of its forces from Afghanistan within the next two years and is handing over security to local forces. They will continue the fight against Taliban insurgents.

But this could mean the armed commanders and their gangs are left to consolidate their power - and many ordinary Afghans will be left at their mercy.

Originally published on Nov. 28, 2012