Over a decade after the September 11, 2001, attacks in the United States and the military campaign in Afghanistan, there is some good news, but still much bad news pertaining to women in Afghanistan. The patterns of politics, military operations, religious fanaticism, patriarchal structures and practices, and insurgent violence continue to threaten girls and women in the most insidious ways. Although women’s rights and freedoms in Afghanistan have finally entered the radar of the international community’s consciousness, they still linger in the margins in many respects. Overall, the situation for girls and women in Afghanistan remains bleak.

INTRODUCTION

The situation for Afghan girls and women remains deplorable, despite concerted efforts to improve their freedoms, rights, and quality of life. In a June 2011 global survey, Afghanistan was named as the “world’s most dangerous country in which to be born a woman.”(1) Afghanistan has staggering maternal mortality rates, poor and inaccessible health care, decades of conflicts, and “near total lack of economic rights,” rendering the country “a very dangerous place for women.”(2) In addition, “women who do attempt to speak out or take on public roles that challenge ingrained gender stereotypes of what is acceptable for women to do or not, such as working as policewomen or news broadcasters, are often intimidated or killed,”(3) according to Antonella Notari of Women Change Makers.

Since the United States toppled the extremist Taliban regime in October 2001, misogynist ideologies, views, and attitudes have not improved. For example, Jaleb Mubin Zarifi, a Northern Alliance member, is quoted on a National Public Radio (NPR) broadcast as saying, “Democracy is un-Islamic,” and immoral behavior by women causes cancer and AIDS: “We know now that the women are not wearing the hijab (headscarf), and look what’s happening–there’s cancer and AIDS everywhere in Afghanistan.”(4) This is illustrative of misogynist views not even attributed to the Taliban. In fact, the Northern Alliance is the “partner” whom the United States and coalition forces aligned with in the battles against the Taliban in 2001. This quote exemplifies anti-women attitudes and views across the board, and not only characteristic of the Taliban. The United States and coalition’s advocacy of women’s rights in Afghanistan has thus faced inherent challenges and hurdles, as reflected in the above quote.

Sahar Gul, a 15-year old girl brutally tortured by her in-laws for refusing prostitution. Sahar's husband used to beat her and denied her enough food. She had had her nails pulled out with pliers and there were burn signs on her body. She suffered from severe mental stress and was in a critical condition. (Photo: RFE/RL)

It must be emphasized that the issue of Afghan women’s rights and freedoms did not become a worldwide, and particularly a Western concern, until the September 11, 2001, attacks and the subsequent U.S. military campaign in Afghanistan, which successfully overthrew the Taliban regime. The U.S. and international donors committed to Afghanistan’s reconstruction have been active lately in promoting Afghan women’s rights and supporting nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), UN agencies, and some government entities in the efforts to empower Afghan women politically, economically, educationally, and even in law enforcement. However, sociocultural and extremist religious elements continue to pose serious obstacles to these efforts. These constraints and impediments have an immensely devastating impact on the lives of girls and women in Afghanistan, and most often result in severely impairing quality of life and even reducing female life expectancy.

Another ominous trend that has undermined Afghan women’s rights is President Hamid Karzai’s political constituency, consisting of increasingly conservative(5) and fundamentalist characters. In order to appease them and gain political support, the Karzai government has compromised women’s rights. In some cases, it has even cast a symbolic vote to Taliban-like mindsets. Meanwhile, women politicians, activists, and journalists constantly face intimidation and threats, and a number have even been assassinated.

One glance at the health and education statistics pertaining to Afghan girls and women alone is enough to see that improvements have been painfully gradual, and attention to these harsh realities has been grossly deficient. This paper examines these health and education variables, as well as the government policymaking that has triggered setbacks in women’s rights. Trends in violence against women and insecurity are also analyzed.

All of the variables that negatively affect the lives of girls and women in Afghanistan are interconnected and interdependent. Therefore, none of them can afford to be overlooked. Overall, the situation for girls and women in Afghanistan remains bleak and tragic (Figure 1 provides a map of Afghanistan).

HEALTH INDICATORS

Afghanistan’s life expectancy and maternal and infant mortality rates are the lowest in the world, with only some parts of sub-Saharan Africa faring slightly worse. Health indicators for Afghanistan, especially for females, are definitely the worst within the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), whose other members include Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, and the Maldives.

Afghanistan is the second worse place to become a mother. (Photo: IRIN)

Perinatal conditions account for the number one health-related cause of death in Afghanistan. Perinatal conditions are defined as the “period around childbirth, especially the period beginning five months before delivery and ending one month after delivery.”(6) In Afghanistan, 13 percent of all deaths are attributed to perinatal conditions.(7) Perinatal conditions “only affect women, partly explaining the short life expectancy of women and their under-representation in the country’s population.”(8) Afghan women’s life expectancy falls short compared to men. In fact, between 2002 and 2006, female life expectancy actually declined from 44 years in 2002 to 43.3 years in 2006.(9)

Approximately 1,700 Afghan girls or women die in childbirth (per 100,000 live births).(10) This is a staggering maternal mortality rate (MMR), the second highest in the world.(11) The MMR in Afghanistan varies by region and rural and urban areas, and the MMR in Badakshan “is the highest in the world.”(12) High MMR is attributed to lack of access to skilled health professionals during labor and delivery. In Afghanistan, the majority of deliveries occur at home, and usually a skilled health professional is absent.(13) A health professional was present in only 14 percent of deliveries in 2003.(14) There are also other factors affecting MMR, “such as lack of services for maternal health care, violence against women, child marriages, overall poor health, and frequency of childbirth.”(15)

The infant mortality rate (IMR)(16) stood at 140 per 1,000 live births in 2003, and 135 per 1,000 live births in 2007.(17) The under-five mortality rate (U5MR) for 2003 was 230 per 1,000 live births, which is extremely high. “The child mortality rate was being attributed to low literacy among mothers, lack of access to safe drinking water, food, and sanitation.”(18) In addition, due to high child mortality rates, total fertility rates (TFR) also remain high: 7.7 (1970) and 8.0 (1990);(19) 6.3 (2003);(20) and 6.6 (2008).(21)

LITERACY AND EDUCATION

“The best judge of whether or not a country is going to develop is how it treats its women. If it’s educating its girls, if women have equal rights, that country is going to move forward. But if women are oppressed and abused and illiterate, then they’re going to fall behind.” – Barack Obama, Ladies’ Home Journal, September 2008

Afghanistan “has one of the lowest levels of literacy in the world.”(22) For ages six and higher, the overall literacy rate in 2005 was 28 percent.(23) Female literacy rates are considerably lower than males in all provinces; female literacy in 2005 was 18 percent, and male literacy was 36 percent.(24) According to the Ministry of Women’s Affairs (MOWA) and the UN Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM), eleven Afghan provinces have female literacy rates less than 10 percent: Badghis, Ghor, Helmand, Kandahar, Khost, Laghman, Logar, Paktika, Sari Pul, Uruzgan, and Zabul.(25) The nomadic Kuchis’ overall literacy rate is a mere 6 percent.(26) In 2007, the overall literacy rate for ages 15 and higher was 29 percent.(27)

Once again radicals opposing girls’ education on Sunday poisoned more than three dozen schoolgirls in northern Takhar province, the third incident of its kind over the past two months, officials said. (Photo: PAN)

In 2005, the Afghan adult literacy rate was 23 percent; the female adult literacy rate stood at only 11 percent, while the male adult rate was 32 percent.(28) In 2004, the literacy rate for males and females (ages 15 to 24 years) was 50.8 percent and 18.4 percent respectively.(29) Literacy rates for the same age group in 2005 were as follows: overall 31.3 percent; females 19.6 percent, and males 39.9 percent.(30) The 2007 literacy rate (ages 15-24) for males was 50.8 percent, and for females was 18.4 percent. The Afghan literacy rates are the lowest compared to all the SAARC countries, and the Afghan female youth literacy rate declined from 19.6 percent in 2005, to 18.4 percent in 2007. This is an alarming development.

Primary school enrollment figures have improved slightly over the last few years, for both females and males. However, secondary school enrollment rates for females remain dismal. According to UNICEF, the female secondary school enrollment ratio for 2000-2005 was only 5 percent.(31) Retention of girls in secondary schools is a serious problem. In 2005, females in grades 7-9 and high school grades 10-12 comprised 24.1 percent, and males were 75.9 percent. Female enrollment declined from 25 percent in grade 7, to 20.6 percent in grade 12.(32) Tertiary enrollment also decreased from 2 percent (1990) to 1.1 percent (2005) and continues to decline.(33)

In 2004, spending on education accounted for only 1.7 percent of GDP, the lowest in the SAARC. Afghanistan “needs to increase public spending in the education sector to a level above that of India in 2002 (4.1 percent of GDP) in order to catch up with other South Asian countries.”(34)

The main impediments to female education in Afghanistan and among Afghan refugee populations are related to security and safety. The primary security and safety problems in the post-Taliban era include the following:

• Criminal acts and behavior: general lawlessness, warlordism, drug trafficking, and extortion.

• Gender-specific violence, such as rapes, gang rapes, murders, kidnapping, child and forced marriages, and domestic violence and abuse.

• Threats to girls and women from fundamentalists including the Taliban, (Northern Alliance) mujahiddin, al-Qa’ida members, and various mullahs.

• Terrorism (including suicide attacks) and firebombing of schools (especially girls’ schools), the presence of foreign troops battling against the Taliban and al-Qa’ida, and a generally increasing level of violence.

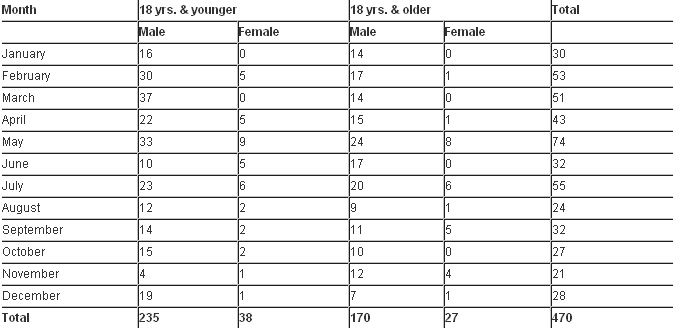

• Landmines and unexploded ordnances (UXOs), dangerous roads, and poor infrastructure (see Table 1: Landmines and Explosive Remnants of War (ERW) January-December 2009).

From Table 1, one can see that landmines and UXOs are serious and dangerous realities of life in Afghanistan. Boys and men clearly suffer more casualties and injuries from landmines and UXOs, but girls and women are not immune. In fact, the numbers in Table 1 indicate that females are kept out of the public space considerably more compared to males. Consider that:

At the orthopedic centre of Wazir Hospital, nine-year-old Wazir Hammond rests against a wall of sandbags that protect the hospital against rockets, shelling and bombs. More than a hundred people, most of them civilians, are killed and maimed every month by land mines in Afghanistan. (Photo: Robert Semeniuk, Kabul, 1996)

Afghanistan is one of the world’s most heavily mined nations. It has one of the highest proportions of disabled people, and this is largely due to the landmines planted extensively throughout the country. Only two of Afghanistan’s twenty-nine provinces are believed to be free of unexploded battlefield detritus. Most mines were laid during the period of Soviet occupation and the subsequent communist regime from 1980-1992, but they were used strategically even during recent strife between the Northern Alliance and the Taliban.

More than 90% of all those injured by landmines in Afghanistan are civilians. According to a survey by the International Committee of the Red Cross, children represent half of all injuries and deaths from landmines in Afghanistan. They are the most vulnerable victims, affected while playing, tending animals, or scavenging. Growing numbers of returning populations are also at risk as they resettle across the country.

The U.S. bombing campaign has unintentionally contributed to the number of unexploded weapons strewn throughout Afghanistan. More than 10% of American bombs dropped did not explode, and demining teams do not yet have training to defuse them.(36)

The year 2008 witnessed some of the highest casualties resulting from landmines and ERW. Children comprised 56% (numbering 393) of the civilian casualties, and boys constituted 342 of the casualties.(37) This can be explained by an increase in ERW incidents among children, particularly boys (up to 33% from 20% in 2007). The number of child casualties deliberately handling the device did not increase. The second largest group was men (280), followed by girls (51), and women (25).(38)

VIOLENCE, INSECURITY, MISOGYNY

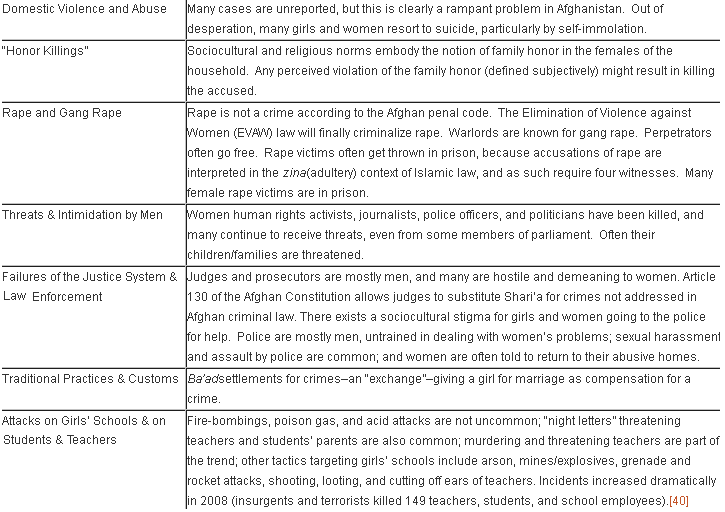

Afghan girls and women suffer from appalling acts of violence, abuse, threats, sexual harassment, and repression. Many crimes go unreported, but even the data that exist are extremely alarming (see Table 2).

SUICIDE EPIDEMICS

Afghan girls and women have been turning to suicide as desperate outlets for their misery. Often, cases involve girls and women who suffer terrible domestic violence and abuse. Many girls resort to self-immolation to escape forced and/or abusive marriages. At least 52 women died from self-immolation in Herat province alone within just a few months (in 2004).(41) “Afghan doctors and officials say at least 184 women brought to Herat’s regional hospital are thought to have set themselves on fire during the past year (2004). More than 60 have died as a result. The real number of self-immolation suicides and attempted suicides is likely to be even higher because only those brought to a hospital are being registered.”(42)

Mariam weeps over her daughter, Najiba, 13. Najiba who had been married six months, claimed that her mother-in-law doused her with gasoline and set her on fire, through her mother, and other nurses in the hospital, were skeptical of her story, and suspected she might have burned herself in an attempted suicide. (Photo: Lynsey Addario/NYTimes)

More photos by Lynsey Addario

More Photos

In a December 2009 interview on World Focus, Rachel Reid, a Human Rights Watch (HRW) researcher, explained the trend of self-immolation, which is especially high in western Afghanistan: “It’s a sign really of quite how desperate some women get. Women and young girls in particular who find themselves trapped in marriages–the majority of girls in Afghanistan are still married below the legal age of 16, and many are forced into that by their parents–domestic violence is very widespread in Afghanistan.”(43)

Reid reports that pharmaceuticals and other forms of suicide are also used. In addition, “as President Karzai has grown weaker and become more dependent on fundamentalist factions there, actually the trends for women and girls can be negative, despite these years of investment and support for Afghanistan.”(44) Very rarely are the abusers and perpetrators punished. Reid says, “The kind of impunity and fundamentalism that’s rife within the politics there is actually as much a part of the problem as anything else.”(45)

DISTURBING TRENDS AND POLICIES

In March 2009, the Afghan parliament passed the Shi’a Personal Status Law, and President Karzai signed it, mainly to gain the Shi’i fundamentalists’ political support.(46) This law “is riddled with Taliban-style misogyny,”(47) as it “regulates the personal affairs of Shia Muslims, including divorce, inheritance, and minimum age of marriage… [and it] severely restricts women’s basic freedoms.”(48) Subsequently, President Karzai issued a decree amending the law, but it still imposes severe restrictions on Shi’i women, including “the requirement that wives seek their husbands’ permission before leaving home except for unspecified ‘reasonable legal reasons.’ The law also gives child custody rights to fathers and grandfathers, not mothers or grandmothers, and allows a husband to cease maintenance to his wife if she does not meet her marital duties, including sexual duties.”(49)

Lal Bibi with her mother in Kunduz, Afghanistan. Lal Bibi said she was kidnapped, locked in a room, beaten, tortured and raped repeatedly by local militiamen, including several who have been identified as members of the American-trained Afghan Local Police. If the daughter's attackers are not punished, she should die, her mother said. (Photo: The New York Times)

Another disturbing trend is the impunity of perpetrators of violence against girls and women. In May 2008, President Karzai pardoned two gang rapists, who are still free today.(50) Countless murderers have never been brought to justice, including those who have killed prominent women. Also, women members of parliament who regularly receive threats do not receive the kind of protection and security detail that their male counterparts are given. Moreover, there is a noticeable increase in fundamentalist attitudes and views among many men in parliament, and some have already voiced opposition to the Elimination of Violence against Women (EVAW) law.(51)

On August 20, 2009, presidential and provincial elections were held in Afghanistan. According to a report by the Afghanistan Independent Election Commission Gender Unit (IEC GU), women’s votes during the election were “used by men and their voting figures inflated.”(52) Hence, the 2009 elections in Afghanistan were marred with fraud: “Patterns of irregularities can be discerned which resulted in the disenfranchisement of women.”(53) The international community has hesitated to push women’s rights issues “due to fear of upsetting the fragile coalition government.”(54)

The “Talibanization” of parts of Pakistan is extremely troubling. The unforgettable April 2009 video of the Taliban flogging a teenage girl in Swat signifies the dangers and mindless violence of that group. They continue to control strongholds in Afghanistan and brazenly operate in parts of Pakistan. The Taliban, Northern Alliance, warlords, and various fundamentalists in Afghanistan and Pakistan perpetuate and strengthen already existing male-dominated patriarchal structures and practices, and they do not hesitate to use violence to exact compliance and spread fear.

Furthermore, civilian casualties resulting from U.S. and NATO-led drone attacks and other conflict-related engagements particularly affect women and children. The Taliban, al-Qa’ida, and other terrorist organizations’ attacks on civilians are also devastating, and even more heinous, as they deliberately target non-combatants. Women and children continue to suffer from unending conflicts in Afghanistan.

POSITIVE DEVELOPMENTS

Initial trends pertaining to Afghanistan’s female population were positive soon after the Taliban regime was toppled, mainly between 2001 and 2005. Of course, the removal of the Taliban itself was a relief for Afghan women and girls. The Bonn Agreement (December 2001) addressed some women’s rights and issues and created the Ministry of Women.(55) Other positive developments have included:

• Ongoing activism and work by various NGOs for women’s rights and issues;

• Heightened activism and resource allocation to women’s issues and gender mainstreaming efforts in Afghanistan from the USAID, U.S. Department of State, and the U.S.-Afghan Women’s Council, as well as various UN agencies, especially the UN Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM);

• The creation of Legal Aid Referral Centers for women provide much needed legal assistance;

• Proactive government agencies and ministries for women’s rights and empowerment, including: the Ministry of Women’s Affairs (MOWA), Ministry of Public Health, Ministry of Education, and the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIHRC);

• Gender-specific plans and actions in: the Afghan National Development Strategy (ANDS), 2006 and 2008; National Action Plan for the Women of Afghanistan (NAPWA), a 10-year plan, drafted in 2005-2006 and approved by the Cabinet in May 2008; and the Gender Budgeting Unit (2007) as part of the Ministry of Finance;

• Ongoing recruitment efforts for female police officers;

• Afghanistan’s ratification (in March 2003) of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), and ratification (in March 1994) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC);

• Quota (25 percent) for women’s representation in the Afghan parliament;

• Forced marriage is considered a crime according to Afghan law;

• Creation of Family Response Units (FRUs), women-only staffs in police stations that serve to: (1) document cases of family violence against girls and women; (2) document cases of sexual violence and child and forced marriages; and (3) provide women law enforcement personnel to deal with women’s problems;

• The passage of the Elimination of Violence against Women law (EVAW), which President Hamid Karzai signed in August 2009;

• President Karzai’s amendment to the March 2009 Shi’a Personal Status law, which toned down the stated restrictions and conditions placed on Shi’i women.(56)

Unfortunately, for each positive development there exist numerous setbacks and shortcomings, and in fact, various post-2005 trends have been negative. Implementation and enforcement of policies, laws, and initiatives are extremely difficult. The principal material deficiency is lack of funding for institutions working for Afghan women. There are also deficiencies in international donors’ allocations for Afghanistan’s reconstruction efforts.

Referring to the George W. Bush administration, Barnett Rubin says, “US policy-makers have misjudged Afghanistan, misjudged Pakistan, and, most of all, misjudged their own capacity to carry out major strategic change on the cheap.”(57) After toppling the Taliban, reconstruction aid to Afghanistan “was only USD $67 a year per Afghan, which is significantly less than what the IMF states allocated to Bosnia ($249) and East Timor ($256).”(58) Currently, U.S. aid to Afghanistan heavily focuses on military operations, and the financial crisis has forced cutbacks. Plus, many international donors’ promises have simply gone unfulfilled. Still, the European Union (EU), the UN, the United States, Italy, Norway, Canada, and Germany, among others, and a wide array of NGOs have been contributing critical resources and providing much needed training in numerous sectors of society in Afghanistan.

CONCLUSION

Although there have been some gains and progress in women’s rights and empowerment in Afghanistan, the obstacles and challenges are exceptionally disheartening. The trends in violence against girls and women are especially discouraging and worrying. Reforming the laws and penal codes, improving the judiciary, aligning the EVAW law more closely with Afghan criminal law, criminalizing rape and redefining it in a way that dissociates it with zina (adultery), building awareness of the plight of girls and women, and facilitating attitudinal shifts toward a more gender balanced society are all imperative. Seeking political expediency at the expense of human rights, especially women’s rights, must stop. Conflict resolution, stability, and security are also critical requisites for rebuilding and reconstruction in Afghanistan. Without the necessary infrastructure and appropriate institutional structures in place, human rights efforts and educational goals will continue to face major challenges and impediments.

While Afghanistan has taken a step forward, at the same time it has been forced several steps back. The international community, along with the Afghan government, has to some extent supported girls’ schools, literacy, and health care, but insurgents, terrorists, thugs, and mullahs continue to block these efforts. More schools close due to threats and attacks. By late 2008, “600 schools were reported closed, 80 percent of them in the southern provinces of Helmand, Kandahar, Zabul, and Uruzgan.”(59) Plus, pervasive chauvinistic and misogynistic attitudes still afflict Afghan society.

The question to ask is: Why are there overwhelming trends of violence against the female population, and calculated misogyny? Although investigating the answer would require connecting the historical dots and deeper analysis of the situation, there are two interrelated variables that can be immediately exposed: Afghan men who engage in violence against the female population, and support policies, decrees, and structures that secure girls and women’s oppressed and strictly controlled position in society, are seeking to (1) sustain their own power bases; and (2) exploit opportunities to accumulate wealth. In other words, sustaining the current political, economic, sociocultural, religious, and tribal systems, and even educational deprivation of the female population, all provide advantages and opportunities for men to earn money and exploit opportunities, legally or illegally (e.g., the drug trade, human trafficking, black market, arms trafficking, as well as legal means of making a living). Empowering girls and women would perceivably take that away from them, or, at a minimum, would force them to share the advantages and opportunities that come with freedom of mobility, education, and self-sufficiency. Hence, maintaining the status quo is the ideal, and many resort to criminal behavior and violence in order to preserve it. The way the status quo operates allows such men to behave criminally with impunity.

The degree of anarchy in Afghanistan and parts of Pakistan undoubtedly supports the status quo. Given greater law and order, security, and stability, there would not be such brazen and pervasive criminal behavior and activities, such as the narcotics industry, human trafficking, and warlordism. The international community is also implicated in this. After all, had countries not invaded Afghanistan and triggered conflicts and wars, and would that consumers worldwide stem their appetites for drugs, prostitution, arms, and other such dark desires, some of the primary sources of power and wealth of the Afghan militias, politicians, warlords, and power brokers would be cut off. There seems to be denial on the part of the international community regarding these uncomfortable truths. Often times, the international community behaves with blissful ignorance toward these matters, as if it need not bear responsibility for the devastation of Afghanistan. This is not to say that Afghans are not complicit in their own destruction. Nonetheless, external actors are not off the hook, nor should they be let off.

The vicious cycle of the lack of education, poverty, illiteracy, and violence and insecurity fueling and supporting the highly patriarchal society, and even fundamentalism and militancy, continues to exist in today’s Afghanistan. Breaking the cycle will take great resolve and courage, as many Afghan women and men have demonstrated, sometimes paying with their lives.

*Hayat Alvi, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor in the National Security Affairs Department at the U.S. Naval War College, Newport, Rhode Island. She specializes in the Middle East, South Asia, and Islamic Studies. She is the author of Regional Integration in the Middle East: An Analysis of Inter-Arab Cooperation (Edwin Mellen Press, 2007), and co-editor of Case Studies in Policy Making, 12th edition (U.S. Naval War College, 2010). She has written extensively about women in Afghanistan.

Notes:

[1] Owen Bowcott, “Afghanistan Worst Place in the World, But India in Top Five,” The Guardian, June 14, 2011, http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/jun/15/worst-place-women-afghanistan-india.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Quil Lawrence, “For Young Afghans, History’s Lessons Lost?” National Public Radio (NPR), September 8, 2011, http://www.npr.org/2011/09/08/140259788/for-young-afghans-historys-lessons-lost.

[5] Although much of the literature pertaining to Afghan women’s rights refers to so-called “conservative” elements that oppose women’s empowerment, the current author contests this characterization and terminology. It is not simply conservative mindsets, but blatantly sexist, chauvinistic, and misogynistic individuals and groups who mask their prejudices behind the fašade of ultra-orthodox interpretations of cultural and religious norms. They deserve to be called misogynists.

[6] “Women and Men in Afghanistan: Baseline Statistics on Gender,” Afghanistan Ministry of Women’s Affairs (MOWA), United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM), 2008, p. 42.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid., p. 35.

[10] “We Have the Promises of the World: Women’s Rights in Afghanistan,” Human Rights Watch (HRW), December 2009, p. 51. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), maternal health “refers to the health of women during pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period. While motherhood is often a positive and fulfilling experience, for too many women it is associated with suffering, ill-health and even death. The major direct causes of maternal morbidity and mortality include hemorrhage, infection, high blood pressure, unsafe abortion, and obstructed labor.” See “Maternal Health,” World Health Organization (WHO), 2010, http://www.who.int/topics/maternal_health/en/.

[11] Surpassed only by Sierra Leone.

[12] “Women and Men in Afghanistan,” p. 37.

[13] Ibid., p. 39.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid., p. 37.

[16] IMR refers to an infant’s death between the day of birth and 12 months of age.

[17] Ibid., p. 36.

[18] Ibid.

[19] UNICEF–Afghanistan–Statistics, http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/afghanistan_statistics.html.

[20] “Women and Men in Afghanistan,” pp. 37, 39.

[21] UNICEF–Afghanistan–Statistics.

[22] “Women and Men in Afghanistan,” p. 47.

[23] Ibid., p. 49.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid., p. 50.

[27] Hayat Alvi, “A Progress Report on Women’s Education in Post-Taliban Afghanistan,” International Journal of Lifelong Education (JLLE), Vol. 27, No. 2 (March/April 2008), p. 173.

[28] “Women and Men in Afghanistan,” p. 50.

[29] Alvi, ““A Progress Report on Women’s Education in Post-Taliban Afghanistan,” p. 173.

[30] “Women and Men in Afghanistan,” p. 51.

[31] Alvi, “A Progress Report on Women’s Education in Post-Taliban Afghanistan,” p. 171.

[32] “Women and Men in Afghanistan,” p. 47.

[33] Alvi, “A Progress Report on Women’s Education in Post-Taliban Afghanistan,” p. 173.

[34] “Women and Men in Afghanistan,” p. 55.

[35] “Farmers and Villagers Help Rid Communities of Landmines,” Afghanistan Conflict Monitor, Human Security Report Project, February 4, 2010, http://www.afghanconflictmonitor.org/landmines/.

[36] “Afghanistan’s Health Crisis,” in Afghanistan Year 1380, POV-PBS, September 9, 2002, http://www.pbs.org/pov/afghanistanyear1380/health_crisis.php#ABC.

[37] “Afghanistan: 2008 Key Data,” Landmine Monitor, International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL), 2009, http://www.lm.icbl.org/index.php/publications/display?act=submit&pqs_year=2009&pqs_type=lm&pqs_report=afghanistan&pqs_section=.

[38] Ibid.

[39] A valuable source for this is: “We Have the Promises of the World.”

[40] See “Education under Attack 2010–Afghanistan,” Refworld Refugee Decision Support, UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 2010, http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/4b7aa9e6c.html.

[41] See Martin Patience, “Afghan Women Who Turn to Immolation,” BBC News, March 19, 2009, http://www.news.bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/-/2/hi/south_asia/7942819.stm; and Ron Synovitz, “Afghanistan: Self-Immolation by Women in Herat Continues at Alarming Rate,” Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty, February 4, 2005, http://www.rferl.org.

[42] Synovitz, “Afghanistan.”

[43] Rachel Reid, Interview, “Women in Afghanistan Turn to Self-Immolation over Abuse,” World Focus, December 3, 2009, http://worldfocus.org/blog/2009/12/03/women-in-afghanistan-turn-to-self-immolation-over-abuse/8729/.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Ibid. See also David Chater, “Domestic Abuse in Afghanistan: Women Burn Themselves to Death,” Al Jazeera, November 29, 2009, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x4WkEc21MWg&feature=player_embedded.

[46] “We Have the Promises of the World,” p. 3.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Ibid., p. 36.

[51] Ibid., entire report.

[52] “One Step Forward, Two Steps Back? Lessons Learnt on Women’s Participation in the 2009 Afghanistan Elections,” A Report from a workshop convened at the Resource Center for Women in Politics, Kabul, Afghanistan, by the Gender Unit of the Afghan Independent Election Commission (IEC) and UN Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM), October 19, 2009, p. 2.

[53] Ibid., p. 5.

[54] Katherine Hubbard, “Disturbing Trends toward Violence against Women in Afghanistan,” Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), January 14, 2010, http://csis.org/blog/disturbing-trends-toward-violence-against-women-afghanistan.

[55] Not all women were pleased with the Bonn summit’s outcomes, especially the power-sharing deal with the Northern Alliance (NA), which includes war criminals, notorious warlords, drug traffickers, and rapists.

[56] See “We Have the Promises of the World.”

[57] Barnett Rubin, “Saving Afghanistan,” Foreign Affairs, January/February 2007, http://www.foreignaffairs.org.

[58] Alvi, “A Progress Report on Women’s Education in Post-Taliban Afghanistan,” p. 170.

[59] “Education under Attack 2010.”