By Arianna Huffington

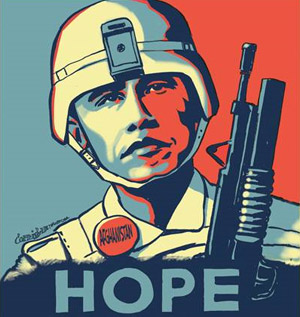

In the last month, the United States hit three milestones in the war in Afghanistan. In late September, the 33,000 additional soldiers that President Obama ordered to Afghanistan in late 2009 came home, leaving 68,000 troops in the country as part of the 108,000-person NATO force. Also last month, the number of U.S. soldiers killed reached 2,000. And this past Sunday marked the 11th anniversary of the longest war in American history. Unfortunately, one milestone the U.S. has not yet hit is the answer to the question: Why on earth are we still there?

Maybe it's because, in addition to being America's longest war, Afghanistan is a contender for being America's least-talked-about war. In President Obama's weekly radio address, delivered the day before the 11th anniversary of the war, the word "Afghanistan" wasn't spoken a single time. Nor did we hear it once during Mitt Romney's acceptance speech at the Republican convention. Even though our presence in Afghanistan is a big drain on America's budget, in the first presidential debate last week the word came up exactly once, in the context of President Obama boasting about how he's willing to "take ideas from anybody," which is "how we're going to wind down the war in Afghanistan."

Yes, we're winding it down -- by the end of... 2014. But how many American soldiers are going to die between now and then? If we know we're leaving, and we don't know why we're staying, it makes each additional death until then seem especially sad and cruel. Right now, American and coalition troops are dying at a rate of about one a day. That puts the 800 or so days until we're scheduled to completely withdraw into a more sobering context. To paraphrase a young, newly-returned-from-Vietnam John Kerry: "How do you ask a man to be the last man to die because of an arbitrarily and pointlessly chosen withdrawal date?"

As we prepare to add over two years to our record 11-year war, let's look at some results from the first decade:

In addition to the 2,000 American dead, there have been over 1,000 coalition forces killed.

Over 17,000 American soldiers have been wounded.

As of October, 2012 ranks as the 4th deadliest year for American troops.

There have been an estimated 20,000 Afghan civilians killed.

Over 3,200 American troops have been diagnosed with Traumatic Brain Injury.

And as our senior military correspondent David Wood writes, these numbers "necessarily fall far short of the true cost of young lives cut off, of grieving families, of children without a parent."

Factoring in the war in Iraq, another war waged on a false rationale, the U.S. has spent around $1.4 trillion so far -- a fact one would think might come up in a presidential debate devoted to the economy.

And as for the surge? Nearly 1,000 of those American soldiers were killed or died of combat injuries since the surge was announced. What's more, as Spencer Ackerman writes, "according to most of the yardsticks chosen by the military -- but not all -- the surge in Afghanistan fell short of its stated goal: stopping the Taliban's momentum."

For instance, in August 2009, shortly before the surge began, there were 2,700 attacks on U.S. and allied troops. In August of this year there were almost 3,000.

In August 2009, there were nearly 600 homemade bombs used against U.S. and allied troops. In August 2012? Over 600.

Nor did the surge help with the larger political goals of NATO and the U.S. As Matthew Rosenberg and Rod Nordland put it in the New York Times last week:

"With the surge of American troops over and the Taliban still a potent threat, American generals and civilian officials acknowledge that they have all but written off what was once one of the cornerstones of their strategy to end the war here: battering the Taliban into a peace deal."

The new objective is the "far more modest goal" of "setting the stage for the Afghans to work out a deal among themselves" after the U.S. leaves. How's that going? "I don't see it happening in the next couple years," says a senior allied officer.

And setting the stage, of course, means training the Afghans to take over the effort for themselves. But even that's breaking down, partially because of the increasing instance of "green-on-blue" attacks -- i.e. Afghan troops killing their U.S. or allied trainers. So far this year, 52 U.S. or NATO troops have been killed in such attacks, accounting for one in five U.S. and NATO combat deaths.

The assaults have led to the U.S. halting much of the training program while it vets -- again -- the background of all 350,000 Afghan forces. "The Taliban have found a niche," said former Ambassador to Afghanistan Ryan Crocker. "And our own vetting in the U.S. military is not that great, let's face it." So much for setting the stage. Maybe we can lower the bar even more to "setting the stage to set the stage."

One such green-on-blue casualty was 21-year-old Army mechanic Mabry Anders, who was killed last month. His mother was called at her office to inform her that two soldiers were at her door. "I served in the Army myself," she said. "We knew why they were here." Anders' hometown newspaper ran an editorial that said that his death has "erased our collective complacency" about the war. That may be true in Baker City, Oregon, but it doesn't seem to be true for the nation as a whole.

After all, the war has barely come up during a campaign that already seems interminable. Will it come up in the vice-presidential debate tonight, or in the next presidential debate?* It will of course come up on October 22nd, when the debate is devoted to foreign policy. But there most likely won't be any actual debate. "I will pursue a real and successful transition to Afghan security forces by the end of 2014," said Romney in his major foreign policy speech this week at the Virginia Military Institute. "This is precisely the same position the current Administration takes," writes Zack Beauchamp. "Romney surrogates have been unable to point to one specific difference between Obama and Romney on our largest ongoing war."

So again, why are we there? The patriotic bromides ("finest military in the world") and Pentagon jargon ("as their troops stand up, we'll stand down") are all standard issue, but in this instance they're particularly dangerous because they serve to obscure the harsh reality of what's actually going on over there.

What can we do? At the very least, we must shake off our collective complacency about our longest war, and force our leaders to explain, exactly, why it needs to be any longer.

*Update (10/12/2012): Afghanistan did come up in the vice presidential debate, but there was no real answer from either Biden or Ryan to Martha Raddatz's question, "Why not leave now?" Instead, Ryan simply said that "we agree with a 2014 transition," and Raddatz asked Biden about "senior officers" who objected to pulling the surge troops out.