The Wall Street Journal, February 22, 2012

Afghanistan Targets Flight of Cash

Central Banker Vows to Stem Exodus of Dollars, Riyals; Tough Law to Enforce

By Yaroslav Trofimov

Afghanistan's central-bank governor said he will issue new currency restrictions to stem an exodus of billions of dollars in cash—some of it in stolen U.S. aid and drug money—flowing out of the country as foreign forces withdraw.

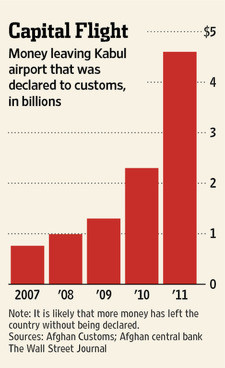

Some $4.6 billion in cash, more than the entire government budget, was taken abroad through Kabul airport alone last year, according to Afghan central-bank data, double the $2.3 billion recorded in 2010. But even those figures "grossly" underestimate the real extent of overall money flight, central-bank governor Noorullah Delawari said in an interview.

"We want to restrict the physical transfer of cash beyond our borders," Mr. Delawari said. "This transport of money does not benefit us. We want to prevent the misuse of currencies for terrorism or money laundering."

Any amount of cash can be carried through the Kabul airport under current rules, as long as the transporter makes a customs declaration.

Every day, money couriers clutching suitcases full of dollars, euros, Saudi riyals and other currencies pack flights to Dubai, many of them transferring funds on behalf of traditional "hawala" exchange networks. A substantial part of that cash, officials say, is first smuggled into Kabul from Pakistan, which has more stringent currency rules.

Afghanistan, one of the world's poorest and most corrupt countries, produces more than 90% of the world's illicit opium. Its economy is largely dependent on foreign aid—billions of dollars of which U.S. investigators say have been lost to graft and misuse. The U.S. has long been pressuring Afghanistan to crack down on money laundering and terrorism financing, pressure that has come up against resistance from entrenched interests in Kabul.

Afghan officials promised to clean up the country's financial system in 2010, when a Wall Street Journal report about large amounts of cash exiting the Kabul airport prompted the U.S. Congress to temporarily freeze American assistance to Afghanistan.

But the money flow to Dubai and other financial havens has only gathered speed as U.S. forces begin to pull out ahead of the 2014 deadline for transferring security responsibilities to the Afghan government. The unfolding drawdown has already begun to squeeze Afghanistan's economy, with property prices in Kabul plunging as Western aid projects dry up, and as many wealthy Afghans choose to squirrel their money abroad, fearing a civil war.

Mr. Delawari, a former banker at Lloyds Bank in California, was appointed in late November, after his predecessor fled Afghanistan amid a corruption investigation into the collapse of the country's biggest privately owned bank, Kabul Bank.

A new regulation Mr. Delawari is preparing will limit the amount of physical cash any individual can transport abroad to $20,000 per trip. There would be no restrictions on transfers through the banking system. "If money is caught being transported, it will be illegal, and it will be confiscated," he said.

It isn't clear what immediate effect the new rules will have in Afghanistan, with well-connected drug mafias and the traditional hawala money-transfer networks certain to try evading the ban, officials say.

The proposal was met with dismay in Kabul's riverside Saray-e-Shahzada market, the hub of the nation's hawala business, where hundreds of money-changers with brick-size packs of $100 bills in their hands negotiated transactions under snow-covered umbrellas.

"How can they enact these regulations if we don't have any trustworthy banks?" wondered Najeeb Ullah Akhtary, owner of the Akhtaries hawala and president of the hawala owners' association. He pointed to the fact that Kabul Bank was nationalized and bailed out by the government last year after it made hundreds of millions of dollars in fraudulent loans to its shareholders, key among them the brothers of the president and vice president.

"We are a cash-based country that doesn't have any industry," Mr. Akhtary said, predicting severe economic dislocation. "It's not about the money-chargers, it's about the economy."

Many hawala clients are Afghan businessmen who need quick transfers to Dubai to pay for goods they import, explained Ahmad Shah Hakimi, owner of another prominent hawala in the market and deputy chairman of the Kabul Chamber of Commerce and Industry. "The banks can't guarantee a transfer in 24 hours, and we can," he said. "The money that's going out is the foreign aid money, and the money of traders."

Mr. Hakimi and his hawala, the Ahmad Shah Exchange, were blacklisted a year ago under the U.S. Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Act, which outlaws any transactions with U.S. persons and entities. Mr. Hakimi, who says all of his business is legitimate, and his firm continue to do brisk cross-border business.

According to Afghan central-bank figures for July-November 2011, based on customs forms filed at the Kabul airport, 38% of the cash taken out of Afghanistan was denominated in Saudi riyals, 42% in U.S. dollars and the rest in United Arab Emirates dirhams, euros, British pounds and other currencies. Only a few million dollars a year enter through Kabul customs, the bank says.

Mr. Delawari, the central-bank governor, said he was puzzled by the heavy use of the Saudi riyals. Some Western diplomats speculated it could be explained by widespread donations in favor of the Taliban that are collected in Saudi Arabia's mosques. Money traders in Kabul dismissed this theory, saying that high-denomination riyal bills are simply easier to smuggle from Pakistan than the Pakistani rupees.

Mr. Delawari said he is discussing details of the regulation with Afghan law-enforcement agencies before promulgating it, but said he will move ahead despite several powerful interest groups opposing the move. "We're not going to yield to the lobbies," he said. "This is a very important matter."

Law-enforcement officials say enforcement will be a challenge. "The central bank is thinking about the Kabul airport, where we have scanners and can exercise control, said Gen. Baz Mohammad Ahmadi, deputy interior minister commander of the counter-narcotics police. "But this country has many other airports, and many other ways and routes to smuggle out the cash,"

Hawala owners predict their business will survive the planned ban on transporting cash, with customers simply picking up the additional cost of circumventing the law and bribing border officials.

Right now, it costs $50 to $100 to carry $100,000 in cash to Dubai, Mr. Hakimi, the hawala owner, said. If the ban is enacted, he estimated, the transfer fees will rise to $4,000.

Dion Nissenbaum and Matt Murray contributed to this article.

Characters Count: 7653