By Nathan Hodge

The U.S. has wasted or misspent $34 billion contracting for services in Iraq and Afghanistan, according to a draft report by a bipartisan congressional panel, the most comprehensive effort so far to tally the overall cost of a decade of battlefield contracting in America's two big wars.

The three-year investigation comes from the Commission on Wartime Contracting in Iraq and Afghanistan, which was established by Congress in 2008.

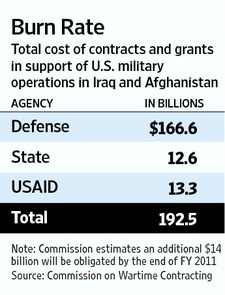

Its final report, expected to be sent to Capitol Hill in the next few weeks, lays out in detail the failure of federal agencies to properly manage and oversee grants and contracts set to exceed a total of $206 billion by the end of the fiscal year on Sept. 30.

The draft report, which was viewed by The Wall Street Journal, identifies myriad instances of projects that were poorly conceived. They include a $300 million U.S. Agency for International Development agricultural development project with a "burn rate" of $1 million a day that paid Afghan farmers to work in their own fields.

It flags diversion of funds to insurgents, such as a subcontractor on a community-development project in eastern Afghanistan paying 20% of their contract to insurgents for "protection." And it touches on cases where the host government was unable to sustain a U.S.-funded project, like a costly water treatment plant in Nasiriya, Iraq, that produced murky water and lacked steady electric power and the construction of an Afghan military academy that would cost $40 million to operate and maintain, far beyond what the Afghan government budget could afford.

Around 75% of the total contract dollars spent to support operations in Iraq and Afghanistan has gone to just 23 major contractors, but the federal work force assigned to oversee those contracts hasn't grown in parallel with the massive growth in wartime expenditures.

The report warns that the eventual withdrawal of U.S. troops and assistance poses the risk of "massive new wastes of money," because both the governments of Iraq and Afghanistan may be poorly prepared to manage projects begun with U.S. taxpayer funds.

Clark Irwin, a spokesman for the panel, declined to comment on the report's total preliminary estimate of wasteful spending, saying the commission was "working on a finalizing an estimate of the range."

Mr. Irwin said the commission had publicly discussed a "conservative estimate" that 10%—or around $20 billion—of the total was likely wasted. That doesn't include losses from unsustainable projects that may be abandoned in the future, or fall victim to fraud. Potential losses, he said, "may be significantly higher" than $20 billion.

The U.S. government depends heavily on what it calls "contingency contracting" to support the war effort in Iraq and Afghanistan. Hired hands do everything from cleaning latrines and serving food on military bases to maintaining and operating sophisticated military equipment. The government has also spent heavily on contracted reconstruction projects, building roads, repairing schools and refurbishing power plants.

The report says the U.S. at one point employed more than 209,000 people in Iraq and Afghanistan. That figure outstrips the total number of U.S. troops currently serving in combat: 46,000 in Iraq and 99,000 in Afghanistan.

The Department of Defense, the U.S. agency that has spent the most on battlefield contracting, didn't respond to requests to comment.

Stuart Bowen, the special inspector general for Iraq reconstruction, said the figures discussed by the commission were in line with his agency's audits of Iraq reconstruction projects.

The 10% estimate of potential waste, he said, was supported by rigorous audits, but estimating losses from poorly sustained projects, he added, was "difficult to measure."

The U.S. government's controversial reliance of private security contractors has been another focus of the commission. The report says the inappropriate use of contract security has at times inadvertently undermined the aims of U.S. foreign policy.

Private security guards have been the most problematic aspect of wartime contracting. In Iraq, a 2007 shooting incident involving security contractor Blackwater (now called Xe Services LLC) sparked a political and diplomatic crisis. Senate investigators last year found evidence that the mostly Afghan force of private security guards the U.S. military depends on to protect convoys and bases in Afghanistan often had ties to criminals, insurgents and local warlords.

The draft report calls for a major overhaul of the way the U.S. employs contractors in wars and crises overseas.

"Delay and inactivity are not good options, for there will be a next contingency, whether the crisis takes the form of overseas hostilities or response to a declared national emergency like a mass-casualty terror attack or natural disaster," the draft says.