By Ann Marlowe

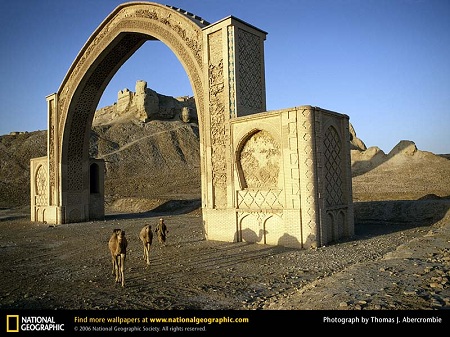

WITHIN a 40-minute drive of this city stands the 11th-century Bost Arch. A former gateway to Lashkar Gah, the capital of Helmand Province, the arch is today a national historic site; it even appears on the 100-afghani note. The arch withstood centuries of invasions, but today it’s a crumbling mess of inept supports and clumsy renovations.

Helmand has been the setting of some of the fiercest fighting in the Afghan war, yet strangely, damage to monuments like the Bost Arch has increased even as the security situation has improved. The problem is that they have gone neglected by the local and national governments, falling prey to squatters, treasure hunters and time. Unless the United States provides money and pressure to protect these national treasures, they will soon disappear.

Camels cast shadows across the Qala-e-Bost arch in southern Afghanistan's Helmand province. The 11th century arch, which appears on the 100 Afghani note, marks the principal approach to the ancient fortress citadel of Bost, later renamed Lashkar Gah. (Photo: Photo shot on assignment for, but not published in, "Afghanistan: Crossroad of Conquerors," September 1968, National Geographic magazine)

Protecting Afghanistan’s heritage sites was never a reason for occupying Afghanistan, but it was always a subtext. After all, the biggest story coming out of the country in the months before 9/11 was the Taliban’s destruction of the Bamian Buddhas, enormous sixth-century statues built into a cliff in central Afghanistan. For those concerned about the fate of the country’s trove of historic sites, the overthrow of the Taliban and the establishment of a democratic government seemed to promise salvation.

Instead, in many places the opposite has occurred. A half-mile from the Bost Arch stand three enormous medieval palaces, the winter residences of the Ghaznavid kings from 976 onward. Now squatters have built crude mud-brick walls within the ancient buildings. A policeman’s family moved in to the most ancient, central palace when their home in Garmsir was destroyed by a bomb. In 1972, when the writer Nancy Hatch Dupree described the central palace in her tourist guide, visitors could explore its second floor; now most of that floor has collapsed.

Between the palaces and the arch stands a magnificent 12th-century octagonal Islamic shrine, the Ziarat-i-Shahzada Husein; even though Afghans continue to pray there, it is decrepit and has no roof.

These aren’t obscure sites, either: the French Archeological Delegation in Afghanistan excavated the palaces in the late 1940s, and it has been pushing the Afghan government for years to request that they be designated a Unesco World Heritage Site.

What explains such neglect? It’s not a lack of resources. Lashkar Gah is set to be one of the first provincial capitals handed over to full Afghan control next month, and the United States has been pouring money into the province. Helmand’s governor, Gulab Mangal, has received $10 million in development funds as a reward for reducing poppy cultivation.

Sadly, that money is unlikely to help preserve the province’s heritage sites. Indeed, the government seems to exist more to expand itself than to serve the people. Muhammad Lal Ahmadi, the governor’s chief of staff, supervises 23 employees, including three who answer letters, two who handle documents, two who handle “relations with other provinces” and two who schedule meetings. This for a poor, rural province of 800,000 people.

The spanking new Government Media Center has a staff of 11. One has the sole job of producing brochures for Helmand’s largely illiterate population — approximately one every three months. Another “monitors media” in a province with no newspaper and just one local TV station.

True, protecting Afghanistan’s historic sites has hardly been a top priority for the United States and its allies, either. But as they begin to plan for a handover of power, it should be. For one, they could press Mr. Mangal to spend more of his money on housing for the squatters who now call the palaces home, and to provide regular security to ensure that vandals and plunderers don’t return. According to Philippe Marquis of the French Archeological Delegation in Afghanistan, stabilizing and securing the palaces would cost around $500,000.

Given the obvious waste in the Helmand government, there’s little doubt the money could be found. And the ruins could be a source of prosperity for Helmand — before Afghanistan descended into chaos, these sites were a magnet for tourists, and with a little renovation and maintenance, they could be again.

American and British diplomats, who carry the most sway in the province, should also help the government in Kabul make the case for designating Lashkar Gah’s monuments a World Heritage Site; winning designation would not only bring the country prestige, but also open the door to Unesco’s own preservation resources.

The United States and its allies have a long to-do list as they plan their slow withdrawal from Afghanistan. But alongside security and government reform should come cultural preservation, which costs relatively little but could result in significant long-term benefits. Otherwise, Afghanistan could experience yet another substantial cultural loss — and this time on our watch.

Ann Marlowe is a visiting fellow at the Hudson Institute.