By Tom Lasseter

Naqibullah was about 14 years old when U.S. troops detained him in December 2002 at a suspected militant's compound in eastern Afghanistan.The weapon he held in his hands hadn't been fired, the troops concluded, and he appeared to have been left behind with a group of cooks and errand boys when a local warlord, tipped to the raid, had fled.

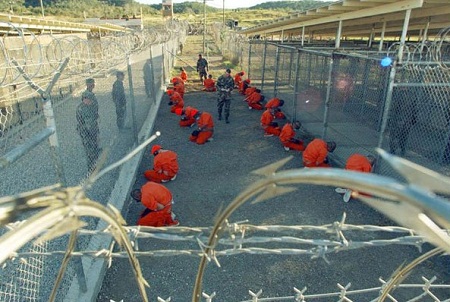

Guantanamo Bay prison camp in Cuba. (Photo: http://www.topnews.in/eu-welcomes-obamas-suspension-guantanamo-prosecutions-2113257)

A secret U.S. intelligence assessment written in 2003 concluded that Naqibullah had been kidnapped and forcibly conscripted by a warring tribe affiliated with the Taliban. The boy told interrogators that during his abduction he had been held at gunpoint by 11 men and raped.

Nonetheless, Naqibullah was held at Guantanamo for a full year.

Afghans make up the largest group by nationality held at the Guantanamo Bay detention center, an estimated 220 men and boys in all. Yet they were frequently found to have had nothing to do with international terrorism, according to more than 750 secret intelligence assessments that were written at Guantanamo between 2002 and 2009. The assessments were obtained by WikiLeaks and passed to McClatchy Newspapers.

In at least 44 cases, U.S. military intelligence officials concluded that detainees had no connection to militant activity at all, a McClatchy Newspapers examination of the assessments, which cover both former and current detainees, found. The number might be even higher, but could not be determined from the information in some assessments, which often were just a few paragraphs long for Afghans who were released in 2002 and 2003.

Still, it's clear from the U.S. military's own assessments that beyond a core of senior Taliban and extremist commanders, the Afghans were in large part a jumble of conscripts, insurgents, criminals and, at times, innocent bystanders. Just 45 were classified as presenting a high threat level, and only 28 were judged to be of high intelligence value. At least 203 have now been released.

U.S. Department of Defense officials have declined to comment on the contents of the WikiLeaks documents, saying they are stolen property and remain classified.

The records contain no single explanation for why so many Afghans with few links to terrorism came to be held at the Guantanamo detention center, a facility that the George W. Bush administration said was intended to house only the most serious of terrorist suspects.

Anecdotes from the documents suggest that many of the Afghan captives were picked up by mistake. Others were passed along to U.S. troops by Afghan warlords and local militias who gave false information about them in return for bounty payments or to set up a local rival.

There was also a desire by U.S. intelligence analysts, particularly in the scramble after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, to cast as wide a net as possible. They were looking to piece together everything from which dirt paths were used to cross between Afghanistan to Pakistan, to the relationship between the Taliban and al-Qaida.

Afghans became crucial for understanding the lay of the land - and for many it cost them years of their lives in confinement.

For at least three Afghan men, the reason listed for being at Guantanamo was a variation of "knowledge of routes between Afghanistan and Pakistan."

The assessments for at least four others listed as the reason for holding them at Guantanamo their knowledge of the Taliban conscription process - meaning they had been forced to join the organization.

"I think many of them were used to get what I call associated intelligence - if they knew somebody who knew somebody who knew somebody," said Emile Nakhleh, the former director of the CIA's Political Islam Strategic Analysis Program who visited Guantanamo to assess detainees there in 2002. "They were the living dots of Google Earth in Afghanistan; we were trying to connect the dots."

The documents, however, undermine Guantanamo's carefully cultivated image as a place where each detainee had been vetted before being sent halfway around the world on a journey for which they were blindfolded, deafened with soundproof headphones and kept in diapers.

Among those held, according to the assessments:

-Haji Faiz Mohammed, a 70-year-old man with senile dementia from Afghanistan's Helmand Province who was detained by U.S. forces during a raid on a mosque where he had been sleeping. A 2002 memorandum for the commander of U.S. Southern Command, barely more than a page long, said that "There is no reason on the record for detainee being transferred to Guantanamo Bay." Mohammed was shipped home later that year.

-Sharbat, the only name by which he is identified in the records, who was arrested by Afghan soldiers after a roadside bomb exploded. His Guantanamo interrogators determined he was an illiterate shepherd who probably was not connected to the explosion. Three interrogation teams at the U.S. detention center at Bagram Airfield also had recommended that he be released. Instead, Sharbat was sent to Guantanamo in November 2003 and held there until February 2006.

-Abdul Salaam's file summarized his case by saying that while he had initially been accused of being a money launderer for militant groups, "after reviewing all of the available documentation, nothing has been found to support this claim. It is highly probable detainee's statements that he and his family are honest business people ... and have never transferred any money for or on behalf of the Taliban or al-Qaida are truthful." He was held at Guantanamo from October 2002 to February 2006.

-Khudai Dad may have been a farmer or he may have had a leadership position in the Taliban. It was hard to assess which was true because the schizophrenic was hospitalized at Guantanamo for "acute symptoms of psychosis" in November 2002 and then referred to the interrogation team for a final interrogation in January 2003.

Eight months later, Guantanamo personnel judged him ready for a polygraph examination. It didn't last long. Dad began having hallucinations in the middle of questioning and the polygrapher "determined he was mentally unfit." His March 2004 report didn't note how long he had been at Guantanamo at that point, but Dad wasn't released until February 2006.

There are lingering questions, too, about whether those identified in the assessments as a serious threat really belonged at Guantanamo.

As the post-invasion period began in Afghanistan, militia commanders - some of them with connections to the Taliban and other insurgent groups - began to jockey for power and to place their men in Afghan security units. By all accounts, those men funneled false information about their enemies to U.S. forces.

(Carol Rosenberg of The Miami Herald contributed to this report.)