By Jason Motlagh and Muhib Habibi

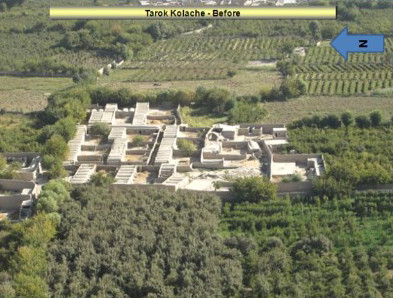

Haji Abdul Hamid pulls out a satellite photograph featuring a cluster of mud-brick compounds engulfed by thick pomegranate orchards. It is labeled "Before." "These were my houses," says the 60-year-old Afghan farmer, outlining a row of buildings. From a bundle of papers he then produces a second image labeled "After" and nods in the direction of an American soldier standing nearby. "They changed it to that," he adds, stabbing at the after image with his finger. There is nothing left.

Before and aftermath: The picture above shows the village of Tarok Kolache in the Arghandab River Valley. The picture below is the same location following after it was hit by 49,200 lb. of U.S. bombs in October last year.

It's been several months since the height of a major U.S. military push to evict the Taliban from the Arghandab valley, a bomb-ridden stronghold in southern Afghanistan. The militants have mostly fled, but a recent blog posting of before-and-after images of Tarok Kolache cast in jarring relief the wholesale destruction that took place there in early October, when it was hit by 49,200 lb. of American bombs. While no civilians appear to have been killed in the village and in two neighboring hamlets that were similarly leveled by air strikes (the residents had been told to leave beforehand), their fate raises fundamental questions about the American strategy and its aftermath: Does the end justify the heavy-handed means? And, is the U.S. military equipped to follow through with reconstruction of such pummeled communities in the long term or predestined to fall short, leaving more anger and insecurity in its wake?

In more than a dozen interviews with displaced residents by a TIME reporter on the scene, locals expressed relief at the absence of the Taliban and the resulting decline in violence. With some exceptions, there is a general if fragile willingness to cooperate with U.S. forces. But it is shaded with doubt over whether the U.S. will make good on big promises to rebuild their village and restore lost livelihoods. Everyone says they had expected damage to their homes, belongings and fruit orchards. However, the total destruction they encountered on returning was a shock.

Fazal Mohammad, 45, spent weeks moving with his family of six between friends' homes, living on handouts and at times spending the night in animal stables. He went back to find his home turned inside out: strips of carpet hanging in the trees, his child's cradle smashed to pieces. Squatting amid the ruins, he rubs his fingers in dirt specked with grains of wheat. "There were two tons of wheat in our store, food for a whole year. But in short time the Americans have mixed it with the earth," he says, his eyes wet with tears. Another returnee, Dad Gul, 62, risked harm from an unexploded improvised explosive device (IED) to salvage a single undamaged possession from the rubble of his former home: an iron pressure cooker.

U.S. military commanders are apologetic yet maintain they had no choice. They say they tried for months to clear the homemade bombs made by the Taliban in the area, but to no avail. Taliban militants had turned several villages into de facto bombmaking factories. IEDs littered the landscape, and the dense, ambush-friendly vegetation made them more difficult to spot. During the campaign, seven U.S. soldiers died and 83 were wounded, most by roadside bombs. To continue moving on foot, officers concluded, was to risk a slow bleed, much as Russian forces had experienced years ago. And because many of the 40-odd buildings were rigged with booby traps, there was no way to ensure that residents warned to leave could return safely once they were cleared. Blowing up Tarok Kolache was the only way to make the place safe again.

Work is now under way to put Tarok Kolache back together, under the supervision of village elders who have set the priorities. A couple hundred local men have been raised to rebuild the mosque and clean area canals and culverts to better irrigate their lands. Wells will be dug out, roads are being improved and there are plans to plant thousands of new fruit trees. With money to be made, "there are lots of people who really want to cooperate with the Americans," says Abdul Qayum, 55, who is taking part in the U.S.-sponsored cash-for-work program. He is paid about $8 a day.

Still, these amount to piecemeal initiatives that employ just a fraction of able-bodied men, whose real expertise is farming. And many residents complain that American officers are offering them far less than what they deserve for their property. (Over $190,000 in compensation has been paid out so far, according to the U.S. military, with more being paid in agreed-upon monthly installments.) Hamid, the farmer with the satellite photos, is not alone in saying that he has yet to receive a dollar and is convinced that, based on the tough nature of negotiations, Americans will ultimately give less than 50% of what they promised. "It won't bring trust," he says.

That's to say nothing of future livelihoods. Apart from losing their homes, area residents are almost entirely farmers whose crops — pomegranates, grapes, mulberries and peaches — were in some cases wiped out. This means they will have no steady source of income for at least five years — the time it takes for freshly planted trees to bear fruit. By then, the current battalion will be long gone, and multiple American units will have come and gone. There's the added possibility that troop levels in the area could be vastly reduced as the 2014 deadline for security transition approaches. Continuity problems, in turn, might undermine security, which is still tenuous.

The killing of Dad Karim, a prominent village malik shot dead by a militant gunman in Kandahar city late last month, suggests the Taliban is down but not out in a region they've always held. Karim had worked with the Americans, and some see his death as a sign the insurgents remain a "ghost power," able to threaten them from the shadows. Over time, some worry the militants will try to regroup and potential discontent over a lackluster reconstruction effort could work to their advantage. The worst of the violence in Arghandab may be over, but the fight for hearts and minds is still under way.