By Nadia Naviwala

A girl was keeled over in pain, silent in her agony. She held herself tightly rocking, head down on her knees. “Sick, sick,” an old woman told us, showing us around the camp. In the neighboring tent, the girl’s newborn was sleeping. She was too sick to feed the baby.

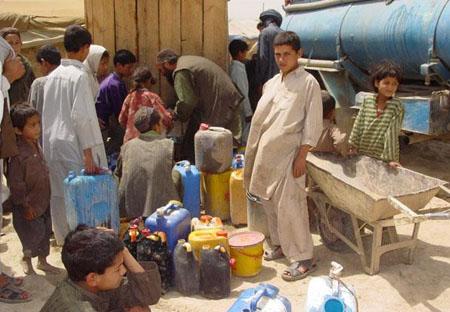

The IDP camps are in a bad condition with no proper running water, electricity or sanitation. (Photo: RAWA.org)

We had asked to be taken to a slum in Kabul, but we were brought to a place that looked like Charahee Qambar, the city’s largest settlement for internally displaced persons (I.D.P.’s).

Helmand

The people in the camp were from southern Helmand province. The woman indicated that they had come to Kabul because of air strikes. She drew her hand across her arms and legs, indicating people who had lost limbs.

Many tents were marked with the letters UNHCR, the United Nations refugee agency. I would have imagined aid workers scrambling about, attending to the displaced. But the camp had been there for two years, nothing more than a forgotten slum: a sea of tents, interrupted occasionally by streams of sewage.

But I was getting used to seeing camps for the internally displaced that looked like slums.

Peshawar

We had flown to Kabul via Peshawar, Pakistan where we visited a camp for I.D.P.s from Bajaur, one of Pakistan’s tribal areas that had been reduced to rubble by Pakistani army operations there 10 months earlier.

The men in the camp told us they had been forced to flee when the Pakistani army bombed and bulldozed their homes. Some said soldiers had looted their homes before bulldozing them, leaving them with nothing but the clothes on their backs. Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy’s Emmy-award winning documentary, Children of the Taliban, depicts how Bajaur was flattened.

We sat on United Nations mats, drinking chai with the women, and they told us they had been forgotten. The people in the camp were living in primitive conditions: no electricity, little or no running water, suffocating heat, inadequate provisions, and children cried at night because of the mosquitoes and the cold. Meanwhile, Pakistan Army operations in Swat and the resulting displacement crisis had captured international headlines, and Swat’s displaced people were receiving truckloads of sympathy and supplies nearby.

Swat

When I later visited U.N. camps for Swat I.D.P.s, they looked as I had originally imagined: clean white tents, with a system to deliver clean water to each one, and electrical lines strung across them. Electric fans whirred, critical in the intense heat. Remarkably, I was told that officials would allow “loadshedding”—Pakistan’s standard, daily electrical outages—in the nearby town, but not in the camps. Even Islamabad does not get electricity 24 hours a day.

But these were new camps, with newly displaced persons. Locals had actually taken most of the I.D.P.s into their homes. But I worried what would happen as local sympathy wore out and international attention, inevitably, faded. Displaced populations seem to live out a certain trajectory—initially welcomed with a surplus of local sympathy, soon forgotten by fatigued donors and caretakers, and finally disparaged as a source of tension and trouble.

The fate of the region’s displaced people is tied to the odds that a stable military victory can be achieved in places like Pakistan’s tribal areas and Afghanistan’s Helmand province. It also hinges on hopes that international entities and local governments will deliver on their promises to rebuild what has been destroyed by war.

But I fear that, for those living in the region’s slum camps, things will never go back to what they were before. And it would not be the first time. When we walked away from Afghanistan after the fall of the Soviet Union, we left Pakistan to deal with the largest population of refugees in the world. Two decades later, these Afghan refugees and their Pakistani-born children are, despite recent repatriation schemes, largely still in Pakistan: permanent, destitute, and unwelcome, their urban camps indistinguishable from slums.

And for those who need more than reasons of human tragedy: the Taliban was born out of Afghan refugee camps in Pakistan, and Pakistan’s displaced populations are already a source of flaring ethnic tensions there.

The most outstanding features of war to those close to the battlefield are its human costs. And while we may ‘care’, in principle and strategy, the promises we make in western capitals easily fall short on the ground. Needs are simply too great, visibility too low, and goodwill too thin. Even if we could commit enough funds to care for the displaced, we are challenged in our capacity to deliver a permanent solution: rebuilding of communities destroyed by war. In this task, we are heavily dependent on local governments that have a spotty record when it comes to performance, particularly in Pakistan where we do not have a direct presence.

As Bajaur’s I.D.P.s face their third winter in the camps, their former homes persist in rubble and the Taliban has resurged — twice. I remember their confusion: Why did this happen to us? When can we go back? As we seek to “win” in Afghanistan and Pakistan, we must remember that a critical part of a sustainable victory is rebuilding. A military victory will mean little to the local population if it means leaving behind more destruction and dispossession in our wake.

Nadia Naviwala is a recent graduate of Harvard Kennedy School. She formerly served as a national security aide to a member of the Senate Armed Services Committee. She wrote a blog about her visits to I.D.P. camps in Pakistan and Afghanistan. In March she contributed an op-ed to the International Herald Tribune, titled Let Pakistan Make Its Own Progress