By David Nakamura

KABUL -- The number of Afghans who are fleeing their country and seeking political asylum abroad has spiked dramatically during the past two years, a sign that people here are giving up the dream of a peaceful homeland to seek security and employment elsewhere.

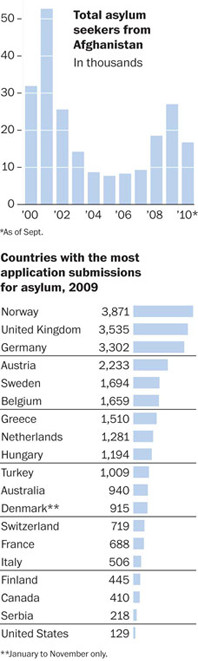

SOURCE: UNHCR | The Washington Post - Nov. 28, 2010

The increase has coincided with a sharp escalation in U.S. troop levels and has made Afghanistan the world's top country of origin for asylum seekers worldwide - ahead of Iraq and Somalia, according to statistics compiled by the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees.

Last year, 27,057 Afghans sought official protection in foreign nations, and although the pace is down this year, the overall trend line could be a troubling indicator as the United States seeks to return Afghanistan to stability.

The vast majority of the refugees are young men in their teens, 20s and 30s, often well educated and with the financial means to pay $20,000 or more to human smugglers for passports and visas to Pakistan or Iran, then on to Europe, Australia, Canada or the United States, immigration officials said.

Among the most capable and brightest of their generation, some are fleeing war-ravaged villages or ethnic tribal violence. But more appear to be pursuing education and higher-paying jobs, sending money home to their families or arranging for relatives to join them abroad.

The common thread among them, human rights activists said, is a growing impatience with the war and a lack of faith that U.S. and NATO forces, which are aiming to hand off authority to Afghan troops by 2014, will prevail against the Taliban.

"What's driving this sharp increase is an uncertainty among the population about the future," said Ahmad Nader Nadery, a commissioner at the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission. "As the discussions about troop withdrawal become much more serious, this is a question of survival. They don't see the current fragility in this government allowing it to make a smooth transition to prevent the Taliban from coming back."

The increase of Afghan refugees has prompted foreign governments to implement stricter immigration controls. In Australia, where 2,705 Afghans have applied for asylum this year, significantly more than last year, officials froze all Afghan cases for six months before lifting the ban in October. Less than one-third of the Afghan applicants in Australia have been granted asylum protection this year.

European countries, which have no unified asylum policy, have deported hundreds of Afghan refugees and kept many more in detention centers or refugee camps for months. Fewer Afghans have applied for asylum in the United States, which immigration officials attributed to the closer proximity of Europe and easier access to South Asian staging points for reaching Australia. In 2010, 113 Afghans applied for asylum in the United States, the most since 2002, according to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service.

High-priced risk

Often the only way out of Afghanistan is a risky journey. Eight Afghans drowned off the coast of Greece last year while trying to reach Europe by boat.

But that doesn't deter people from trying. Hamid Rezayee, 22, is among those thinking of getting out. A recent graduate of northern Afghanistan's Balkh University, where he majored in history, Rezayee dreams of continuing his education abroad to avoid becoming a mechanic like his father and two older brothers.

He and his nine siblings live with their parents in a house in Mazar-i-Sharif, and Rezayee works as a translator for the U.S. Agency for International Development. Though the war has provided him with a job, he speaks of his country with fatigue.

"We have had 35 years of war in Afghanistan, and that has made a very bad situation here," he said.

For the past seven months, Rezayee has sought a path to Australia. Unable to secure a legal student visa, he has turned to smugglers. For $20,000, they told him, he would receive a Pakistani passport and fly from Islamabad to Indonesia. Then he would join other Afghan refugees on a boat to Australia, part of a human smuggling operation that is growing in clout and sophistication, authorities said. Rezayee has begun to save up.

In a report on human smuggling in Afghanistan and Pakistan in January this year, the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime estimated the smuggling industry's annual revenue at $1 billion. The growing network is centered largely in Peshawar, Pakistan, with its Afghan hub based in nearby Jalalabad, according to the report.

"Although smuggling networks are understood as clandestine, many of the industry's activities are quite open in Afghanistan and Pakistan," the report stated. Smugglers create fake documents - including passports, visas, bank statements and education degrees - and provide advice "on how clients should represent themselves fraudulently."

The Afghan government's response, through legislation and law enforcement, "is quite sparse," the U.N. report concluded. In an interview, Abdul Rahim, Afghanistan's deputy minister for refugees and repatriates, said that none of his 1,000 employees is assigned to deal with asylum seekers, nor does any other ministry.

Rahim's department deals instead with the 5 million Afghans who have been repatriated since the war began. Much of the effort is concentrated among the estimated 3 million Afghans who live in Pakistan and Iran but move across the porous Afghanistan border looking for employment.

Many Afghans who have returned home have become disillusioned, said Nassim Majidi, a visiting doctoral candidate at Britain's Oxford University who studies Afghan migration. Of the 100 repatriates she interviewed, 70 told her they were saving money to try to leave again.

This has led some foreign governments to label the Afghan refugees "economic migrants" who are not in danger. But Ahmad Joyenda, an Afghan parliament member from Kabul, said the lack of jobs is tied to the country's insecurity.

"When you cannot find the work to feed your children, to go to school, to do your education, you are still a human being," Joyenda said. "People need to have some secure place for themselves. In this way, it's kind of political-economic migration. It's both."

Seyar, who is in his 30s and spoke on the condition that his last name not be used, recently paid a smuggler $46,000 to send his mother and younger brother to a Scandinavian country.

Seyar met a smuggler in Jalalabad and raised the money by selling his house. The smuggler took Seyar's mother and brother to Peshawar, then to Islamabad.

After receiving travel visas, the two were flown first to London, then to the Scandinavian nation, which Seyar did not want to identify. The brother is in his 20s, but he was instructed to pose as a teenager because the destination country offers more lenient immigration policies for minors.

"I paid that amount of money without knowing a single person" involved in the deal, Seyar said. "I was very worried. I cannot earn that much money in three years."

But it was worth the risk, he decided.

"People have lost hope in American power maintaining peace and stability," he said, "and they've lost faith in the [President Hamid] Karzai administration due to the huge corruption, fraud and nepotism. It is hopeless."