Natalie Bennett

When I was running for the Green Party in the recent British general election, there was one issue on which I had no doubt how audiences at hustings and meetings would react positively – our call to withdraw British (and NATO) troops from Afghanistan. Surveys show around 70% of the public back that stance, and it was close to 100% of the audiences at hustings.

As I told them, I’d had in the past some doubts about our party’s policy of immediate withdrawal, having been worried about the human rights situation that we’d leave behind, particularly for women. But it was a Human Rights Watch report last year, which found 60-80% of the marriages of Afghan women and girls are forced, and learning that the brave women of Rawa are calling for withdrawal that led me to change my mind.

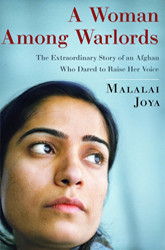

Having just read the autobiography of Malalai Joya, an outstanding Afghan woman MP, I’m now even more strongly of that view. (It was published in the US as A Woman Among Warlords: The Extraordinary Story of an Afghan Who Dared to Raise her Voice.)

She’s an extraordinarily brave, stalwart – and very, very young! — woman who has dedicated her life, and taken enormous risks, to speak out on human rights in her native land. And she says very clearly – and loudly and publicly in her own land, which led to her being expelled from parliament – that the people the U.S. and its allies are backing in Afghanistan are entirely the wrong people, the old warlords, many of them in her eyes (and those of others) war criminals. And she has no doubt that this foreign occupation can only prolong and amplify her nation’s problems.

A Woman Among Warlords, by Malalai Joya

Her story is an extraordinary one. Certainly, she was lucky in her parents, particularly her father, a democracy activist who moved his family around Iran and Pakistan as an exile in search for good schooling for them. (He, like the rest of her family, can’t be identified for their own safety – the name ”Joya” is one she adopted to protect them.) There must be many other potential Malalai Joyas in Afghanistan who will never get that essential foundation or confidence.

But there’s no doubt she was exceptional. Noticed as a fine teacher in the refugee camps, at the age of 21 she was sent to found an underground girls’ school in Herat by the Organisation For Promoting Women’s Capabilities. Only three years later, she was appointed to head its work in three provinces, just before 9/11. Under the new regime, despite its resistance, on her account she set up a clinic, orphanage and was able to distribute food supplies.

She must thus have been well known in the poor isolated province that was to send her, a 25-year-old unmarried woman, as a delegate to the 2003 Loya Jurga (national gathering) that was to approve a new constitution. Still standing for office, addressing a room full of women mostly older than herself, in her first “political speech” must have been quite an experience, and her delicate naivete is touching….

“I had a lot to say, and I wanted to cram those few minutes with everything I had ever done in my life, with everything I believed possible for the future, with everything I wanted for the women of Afghanistan. I stressed that I would never compromise with those criminals who had bloodied the history of our country, and that I would always stand up for democracy and human rights.

“As I spoke, I knew that my message must be getting through, because when the other women were speaking, members of the audience were chatting and making noise and not paying much attention. But as I began to speak everyone quietened down and listened. They even clapped a number of times during my speech…"

Yet, worryingly, as she made her way to the Loya Jirga, she gets strong warnings, not just from Afghans, but from UN officials, not to speak so bluntly there. She says: “Most of them seemed sincerely worried. I am not sure, but it is possible that some of them wanted to scare me into silence.”

Clearly, however, this is not in her nature, and the account of her speech to the Loya Jirga, wrangled and schemed for, then cut short by furious men, abusive women, and protected from physical violence from fellow delegates only by supportive delegates and UN officials. And all of this broadcast to the nation and the world. She’s understandably proud:

“From that moment on, I would never again be safe. At the time, I was not thinking about this, but rather I was pleased that I had been able to expose the true nature of the proceedings. I also began to realise just how much words are powerful weapons and that I had to continue speaking the truth for the sake of the Afghan people who have been silenced for so long.”

That event is about halfway through the book, and in a way after that it is just for Joya more of the same. This is not, however, just a personal story, but the tragic story of a country that’s been very nearly wrecked by foreign interference. It’s not all geopolitics, however, far from it. There’s plenty of anecdotes that illustrate how difficult life was and is for women in Afghanistan, not just forced marriages and lack of medical care, but ordinary, everyday inconveniences and impositions. Under the Taliban, Joya explains, women had to stand up in ice cream shops to eat, and to do so under their burkhas, a ludicrous physical challenge.

And the positive note, the only real hope it seems, for Afghanistan, comes from her accounts of how she, her family and fellow activists have been saved from the Taliban, from the warlords, from the present regime, by simple brave acts by ordinary people. She reports on how her brother had illicitly taken photos of the victim of a Taliban execution, was caught by them, but saved by a camera shop owner who handed over other less dangerous photos of a wedding instead. Another time she reports on how while out after women’s curfew, and hearing a Taliban patrol approaching, she knocked on a random gate and was sheltered by a stranger, a woman, who saw she was carrying schoolbooks but only chided her gently about keeping safe.

If I could prescribe one book for David Cameron, Barack Obama and every other western leader to read over the summer, this would be it. And if I could make a recommendation to the Nobel Peace Prize committee, it would be to follow in the steps of naming Shirin Ebadi as their laureate by choosing another outstanding woman leader.

If you want to understand Afghanistan, what is being done there in our names, this is a highly readable, accessible way to find out. And if I could see a way forward for Afghanistan, it would have Joya in a prominent position.

Natalie Bennett is the editor of My London Your London, an independent cultural guide featuring theatre, gallery and museum reviews, and also blogs at Philobiblon, on history, culture, Green politics and all things feminist. She's the founder of the Carnival of Feminists, and Books Editor on Blogcritics.