B Aunohita Mojumdar

Sakina is angry. "Who is Karzai to forgive the deaths in my family?" she fumes. "Was his home looted? Was his son killed? What gives him the right to forgive on my behalf? He has no right." The source of Sakina's ire is Afghan President Hamid Karzai's reconciliation initiative.

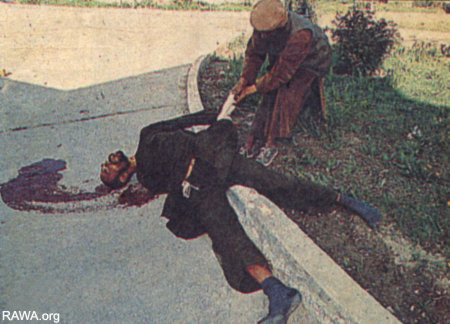

RAWA, April 28, 1992: The "Jehaid" terrorists belonging to Shora-e-Nezar of Ahmad Shah Masoud in action in the Interior Ministry as they entered Kabul after the collapse of Najibullah's government. Thousands of people were killed by the Jehadi warlords during the civil war 1992-96 but today the same criminal warlords occupy the highest positions in the government.

As part of the reconciliation effort, Karzai is supporting an amnesty law that offers blanket immunity to all parties responsible for atrocities committed in Afghanistan over the past three decades, including Taliban militants. Forgiving the Taliban is not something that Sakina is capable of at this point in time. The middle-aged widow from Dasht-e Barchi, a poor neighborhood of west Kabul, lost her husband and niece in the conflict, and feels that Karzai's administration is taking away her right to justice.

"He wants to give the Taliban money, land and privileges. [And] to me, a victim, he gives a widows' pension of 300 afs [afghanis] a month [$6]," continued Sakina. [For background see the Eurasia Insight archive].

In Afghanistan's legislative process, a draft law must be ratified by parliament, signed by the president, and then published in an official gazette before it takes effect. The actual process is sometimes far murkier. Parliament passed a controversial amnesty law - offering immunity to all those involved in past, present and future hostilities, including war crimes or crimes against humanity - in 2007. But the initiative generated considerable opposition from Karzai's international allies and human rights groups who saw it as an attempt by former commanders-turned-MPs to give themselves immunity. Thus, the Reconciliation and General Amnesty Law was not immediately published.

In January of this year, however, news spread that the law had been quietly printed in December of 2008. With the international community now behind Karzai's reconciliation strategy, the government is now apparently hoping that the amnesty law will be accepted without creating too much of a stir.

So far, the international community's muted response suggests Karzai's timing may have been right on. But growing opposition from within Afghanistan, led by human rights and civil society groups, also indicates that the president's reconciliation efforts may soon hit a brick wall.

Opponents of the amnesty law contend that it is unconstitutional. According to a paper prepared jointly by the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission, a body mandated by the Afghan constitution, and the International Center for Transitional Justice, the amnesty law contradicts Kabul's obligations under international law to prosecute serious crimes such as torture, rape, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. Article 7 of the Afghan constitution spells out the country's obligations to abide by international treaties covering war crimes.

Activists describe as especially problematic the "blanket" amnesty from prosecution, which does not make exceptions for war crimes such as rape, torture and genocide; grants immunity for crimes that may be committed in the future; and benefits former combatants who voted for the bill in their current roles as MPs.

[utube]LD4vgVvH24w[/utube]As worded, the law covers "all political factions and hostile parties who were involved in a way or another in hostilities before establishing of the interim administration [in 2001]," as well as "those individuals and groups who are still in opposition to the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan and cease enmity after the enforcement of this resolution and join the process of national reconciliation and respect the constitution and other laws and abide them." Without a cut-off date, the law offers those committing crimes impunity to continue doing so until they please.

As a concession to victims of war crimes, the law provides for individuals to make claims against alleged assailants for specific crimes. However, human rights groups point out that the lack of security and rule of law in Afghanistan makes it almost impossible for individuals to gather evidence and pursue criminal cases against powerful parties involved in the war. "It is fantasy to think that an individual can take on a major war criminal alone," Brad Adams, Asia Director of Human Rights Watch, said in a March 10 statement. "In practice, individuals have severely limited access to the justice system in Afghanistan," he pointed out, adding that the state should not transfer its obligation to investigate and prosecute serious human rights violations to individuals.

The government should immediately suspend the law, argued the Transitional Justice Coordination Group (TJCG), a coalition of 24 Afghan civil society organizations. Group leaders say that, rather than promoting reconciliation and stability, the law, by granting blanket amnesty, "promotes impunity and prevents genuine reconciliation." The coalition seeks "accountability not amnesia for past and present crimes as a prerequisite for genuine reconciliation and peace," the group said in a March 10 statement. "The government of Afghanistan does not have the right to usurp the rights of victims."

The stated purpose of the law is "strengthening the reconciliation and national stability." But the TJCG coalition, human rights groups and analysts view the amnesty law as a political maneuver. "Short-term expediency in the form of reconciliation with the Taliban should not trump the rights of the Afghan people," Amnesty International said in a statement issued in early February. "The legislation is simply an effort to pervert the course of justice under the faulty guise of providing security."

"The existence of this law is as much a test of the principles of Afghanistan's international backers, such as the United States, as it is of Karzai," said Adams of Human Rights Watch. "Will they stand with abusive warlords and insurgents, or will they stand with the Afghan people?"

"It is not for the government to decide," Azaryuon Matin of Human Rights Focus, a member of the TJCG coalition, told EurasiaNet. "Why have they not consulted with civil society [organizations]? If they sacrifice justice, democracy and human rights, there will be no way for rule of law, for human rights, no way for peace."