By Anand Gopal

GARDEZ, AFGHANISTAN - Sitting in an open field, three Taliban-allied insurgents carefully pore over a map of Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan.

The US-led coalition has issued a 200,000-USD reward for the arrest of Sirajuddin Haqqani as part of a Most wanted compaign.

"This is where we will be staying," one says, pointing.

In the next scene from this insurgent propaganda video, one fighter shows the others a video of an empty room with a window. "You will shoot at Karzai from this window," he explains to the others. "We have people on the inside who will help you."

The assassination attempt on President Hamid Karzai, which took place in April 2008 during a military parade, nearly succeeded. The president escaped, but three people died.

The fighters in this video had detailed intelligence of the area. They knew how to slip by police checkpoints, and they had people in the Afghan government telling them exactly where Mr. Karzai would be standing on the parade ground.

Afghan insurgents often film their operations from start to finish, edit the result, and release it as a propaganda video. This video was purchased in Quetta, Pakistan.

Afghan intelligence officials have identified one of the three men in the video as part of the assassination team. All are members of Afghanistan's most lethal group, the Haqqani network, a shadowy outfit that many officials consider to be the biggest threat to the American presence in the country.

"The Haqqani network has proven itself to be the most capable [of the insurgent groups], able to conduct spectacular attacks inside Afghanistan," says Matthew DuPee, researcher at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, Calif.

The network, which is independent of (but allied with) the Taliban, showed its mettle again on May 12, when nearly a dozen fighters stormed government buildings in Afghanistan's southeastern city of Khost. The coordinated attack featured multiple suicide bombers and was one of the most brazen to take place in the city in years.

The Haqqani network is considered the most sophisticated of Afghanistan's insurgent groups. The group is alleged to be behind many high-profile assaults, including a raid on a luxury hotel in Kabul in January 2008 and a massive car bombing of the Indian Embassy in Kabul that left 41 people dead in July 2008.

The group is active in Afghanistan's southeastern provinces – Paktia, Paktika, Khost, Logar, and Ghazni. In parts of Paktika, Khost, and Paktia, they have established parallel governments and control the countryside of many districts. "In Khost, government officials need letters from Haqqani just to move about on the roads in the districts," says Hanif Shah Husseini, a parliamentarian from Khost.

The leadership, according to US and Afghan sources, is based near Miramshah, North Waziristan, in the Pakistani tribal areas. Pakistani authorities and leading Haqqani figures deny this, although former Haqqani fighters say this is indeed the case.

The network is better connected to Pakistani intelligence and Arab jihadist groups than any other Afghan insurgent group, according to American intelligence officials.

These links go back a long way. It was here – in the dusty mountains of Paktia Province, near the Pakistani border – that the group's putative leader, Jalaluddin Haqqani, first rose to fame. Born into an influential clan of the Zadran tribe, Mr. Haqqani morphed into a legendary war hero for his exploits against the Russians in the 1980s. Many in the southeastern provinces of the country fondly recall his name, even those who are now in the government.

"He is a virtuous and noble man, with an unwavering belief in Islam," says Hanif Shah Hosseini, a member of the Afghan parliament from Khost. He is one of Haqqani's childhood friends.

Texas Congressman Charlie Wilson, who worked closely with the anti-Soviet insurgency (inspiring the 2007 Tom Hanks film "Charlie Wilson's War"), once called Haqqani "goodness personified."

In the 1980s, Haqqani quickly established himself as one of the preeminent field commanders. "He could kill Russians like you wouldn't believe," says one US intelligence officer who knew him at the time. The Central Intelligence Agency forged close links with him, and through the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) agency funneled large amounts of weapons and cash his way.

Unlike many commanders, Haqqani was often in the line of fire himself and would at times retreat to Saudi Arabia to convalesce from his wounds. It is believed that his trips to the Gulf helped him forge close links with Arab militants, and he became one of the first Afghan commanders to host foreign fighters. His ties with Arab fighters and Al Qaeda continue to this day, say US and Afghan military officials.

Although he joined the Taliban government in the mid-1990s, Haqqani was never formally part of the Taliban movement. "The Taliban wanted to create an Islamic emirate, but Haqqani favored an Islamic republic," claims Maulavi Saadullah, who was a close friend at the time.

"During those years, [Haqqani's son] Siraj used to complain to me about how heavy-handed and dogmatic the Taliban were in their interpretation of Islam," recalls Waheed Muzjda, an Afghan-based policy analyst who knew the family.

Still, the Taliban saw Haqqani's usefulness as a commander and enlisted him in the fight against the Northern Alliance. On the eve of the American invasion in October 2001, Haqqani was named the head commander for all of the Taliban forces.

But for a few months after the US-led coalition invaded Afghanistan, Haqqani was on the fence as to whether to join the new Afghan government or fight against it, according to those who knew him at the time. A series of American bombing raids killed members of Haqqani's family, and he disappeared across the Pakistani border, telling friends that "the Americans won't let me live in peace," according to Mr. Saadullah. American officials, however, countered that he was abetting Al Qaeda fighters in their escape from Afghanistan into Pakistan and was not a neutral figure.

During the early years of the current Afghan war, Haqqani was merely one Taliban commander among many. But his close ties with Pakistan's ISI and Arab militants enabled him to raise funds and build training camps. Soon he was able to fight independently against the Americans, without help from the Taliban leadership. By 2007 his network had emerged as a distinct insurgent group.

Haqqani's son Sirajuddin has now taken the reins of the organization, according to intelligence officials. The younger Haqqani has proved more dynamic than his father, expanding the network greatly in the last few years. "He is not content with his father's methods," says one US intelligence officer, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. "He's a lot more worldly than his father."

Sirajuddin took credit for planning the assassination attempt on the Afghan president in a rare interview with NBC News in July 2008.

The father has been reported to be dead, ailing, or incapacitated in some way. He last appeared in a March 2008 propaganda video of another insurgent attack.

Unlike most of the Afghan Taliban, the Haqqani network often works closely with foreign militant groups. For instance, the Islamic Jihad Union, an Uzbek militant group, reportedly has ties to the Haqqanis. The IJU brings militants from as far afield as Turkey to conduct attacks in Afghanistan. They are also allegedly behind plots to attack targets in Europe.

The Haqqani network also works more closely with the Pakistani Taliban than other Afghan insurgent groups. (See accompanying story, right.)

The Haqqanis pioneered the use of suicide attacks in Afghanistan, an import from Al Qaeda in Iraq. Haqqani attacks are more likely to use foreign bombers, whereas Afghan Taliban attacks tend to rely on locals. The suicide attacks are an innovation of Sirajuddin's, according to US intelligence officials.

In addition to suicide attacks, the Haqqanis are known for their well-orchestrated attacks. US intelligence officials and Haqqani insiders say that this is largely a result of close cooperation with the Pakistani ISI – something Pakistani officials have denied.

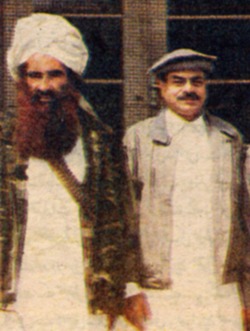

Jalaluddin Haqqani with Gen. (R) Hamid Gul, former director general of Pakistani ISI.

Every major attack "is planned in detail with the ISI in camps in Waziristan," says one former Haqqani commander, who declined to be named for fear of retribution. Officials say the Haqqanis use money from Al Qaeda-linked sources, and also possibly from timber smuggling, to finance their operations.

"The majority of Haqqani fighters are young," says the former Haqqani commander, "and their fathers had fought for Haqqani during the Russian jihad." Many joined after the Afghan government and the Americans failed to live up to their promises, he adds.

Here in Paktia Province, the Haqqani network is so extensive that some subcommanders have emerged as nearly distinct threats in their own right. For instance, longtime commander Saif Rahman Mansour, who had been fighting under Haqqani's banner, has been operating more independently of late, Afghan government officials say.

A WOULD-BE SUICIDE BOMBER’S TALE

‘Ahmad’ tells of his recruitment, indoctrination, assignment, and betrayal.

The case of one captured Haqqani suicide bomber illustrates the closeness of Haqqani's ties to Pakistan.

Ahmad, who asked that his real name not be used for fear of retribution, was born in a small town in Pakistan's Punjab Province. He came from a large but poor family. Pakistan's notoriously poor education system meant that good schools were out of reach, and he instead went to a madrasa– an Islamic school – in his home village.

After this religious schooling, he took a job in a bakery and supported his entire family. "Then one day a friend invited me to take a trip to Waziristan. I knew almost nothing about the Taliban or America at that time," he recalls.

His friend took him to a Pakistani Taliban camp, where his hosts welcomed him and gave him lodging. At first he wanted to leave, but his hosts asked him to stay for a short while and "learn about Islam."

In the morning and afternoon they would recite verses from the Koran, and in the evening they showed him hour upon hour of films of alleged American atrocities in Iraq and Afghanistan.

"I became outraged when I saw video clips of what was happening to my Muslim brothers and sisters," he says. "After watching this for nearly two months, it became intolerable for me. I eventually decided to give my life for my [Muslim] country."

The camp belonged to Maulavi Nazeer, a powerful Pakistani Taliban commander. According to Ahmad, many of the fighters trained under Mr. Nazeer and then went to Afghanistan to fight with the Haqqanis. Ahmad's destiny was not to become a fighter, however: He told his hosts that he would like to become a "martyr," a suicide bomber.

Nearly seven months passed, then one day Nazeer came to Ahmad and told him that he had a job for him.

Some of Nazeer's men drove Ahmad to the Afghan border. On the other side, he was met by Haqqani representatives, who led him to a car full of explosives and a suicide vest. "They told me to drive down a particular road for a short while, after which I would find some foreign soldiers who had killed many Muslims," he recalls.

"I drove and eventually neared a checkpoint with soldiers. My finger was on the trigger – but then I heard them speaking an Afghan language."

The checkpoint was manned by Afghan soldiers, not Americans.

"I realized that I had been tricked. I didn't want to sacrifice myself to kill other Muslims, only the foreign occupiers," he says. "I had my finger on the trigger, but I couldn't press the button."

Ahmad turned himself in and is today in the custody of Afghan authorities.