Heidi Vogt

Millions of new textbooks promised and paid for by the U.S. and other foreign donors have not been delivered to schools in Afghanistan, The Associated Press has found. Other books were so poorly made they are already falling apart.

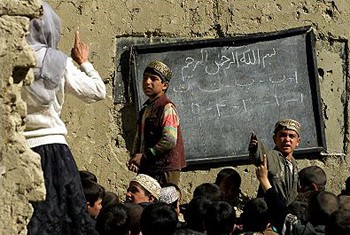

"It's like we're starting out a building with a bad foundation, and we're going to end up with a leaning, crooked structure," said Reza Adda, the education director for Bamiyan province, which she said didn't get 40 percent of the books expected last year. (Photo: Jim Hollander – Reuters)

The faltering effort is testimony to how much can be lost to corruption, inefficiency and bureaucracy in this tumultuous country, where it is difficult to get even the most straightforward aid project done.

About a third of the school books ordered for 2008 were never delivered to the provinces, the AP learned in interviews with officials from all 34 provinces and examinations of Education Ministry records and contract documents.

At the Mir Bacha Kot school for girls outside Kabul, there is no sixth-grade English class, because there are no sixth-grade English texts. Working in one of the tent classrooms scattered across a field, students pore over worn-out fifth-grade books instead.

"It's like we're starting out a building with a bad foundation, and we're going to end up with a leaning, crooked structure," said Reza Adda, the education director for Bamiyan province, which she said didn't get 40 percent of the books expected last year.

If they don't come soon, families may give up on the schools, Adda said.

Only a handful of students in his son's third-grade class got books this year, so day laborer Sayed Sekander spent more than a half day's pay on texts for the boy, shopping like many others in Afghanistan's capital for sometimes illegal copies from market vendors.

"My son told me, 'I have to have books so that I can pass the tests,'" Sekander said.

But he said he will wait before buying books for his two daughters.

Missing textbooks only compound the troubles of the education system in Afghanistan, which suffers from a shortage of trained teachers. In Bamiyan, some teachers just graduated from sixth or seventh grade themselves, Adda said.

There are problems, too, even when books do make it to classrooms. Many are often printed on thin paper, glued instead of stitched, and full of errors, school officials said.

"Sometimes when a child tries to turn the page, it tears off in his hand," said Fida Mohammad Qurishi, the education director for eastern Nuristan province.

Qurishi said teachers are advised to tell students: "When you are turning the page, turn it very slowly. Otherwise it will tear and you will miss something and not be able to do your homework." The Education Ministry says books are supposed to last at least three years.

About 45 million books were scheduled to arrive before classes started in March last year, paid for by the United Nations and the aid agencies of the U.S. and Danish governments at a total cost of $15.4 million.

But there were delays even before a printing contract was signed. And that was just the beginning of the troubles.

"The editing process took more than a year," said Anita Anastacio, whose community education program uses government books. The books were edited and re-edited because a 2006 print run had produced copies full of mistakes, she said.

Some book templates weren't finished until last May, said Abdul Zahir Gulistani, director of curriculum development.

About 600,000 sixth-grade social studies texts were delayed so long that the Education Ministry canceled the print order, according to Angel Allied, the Indian company contracted to print the books.

As it became clear textbooks would come very late, the Education Ministry asked the U.S. military to help.

U.S. forces delivered 13.5 million books in July, at a cost of $7 million. But many of those texts didn't make it to schools until students were starting final exams three months later.

Meanwhile, other printers also missed deadlines, and about 170,000 books that were badly glued had to be redone, Danish officials said.

As books began arriving in Kabul, the Education Ministry found many were printed with pages upside down or contained pages from several texts. Errors like that led the government to reject 1 million books outright, ministry spokesman Asif Nang said.

Problems didn't end there. Distribution snags also slow books getting to schools.

About 500,000 books are in seven shipping containers in Pakistan awaiting customs clearance by the Afghan government, according to Angel Allied. And the Education Ministry said 20 million books are sitting in a warehouse in Kabul while a distribution plan is worked out.

The donors --the U.S., Denmark and the U.N.-- say their job is to provide the money, and the Education Ministry is supposed to look after distribution. U.S. directors of the program say the idea is to put Afghanistan's government in charge of education.

USAID, the American government aid agency, said it received a report saying the 12.7 million books for which it paid $5.2 million were printed, but it doesn't track distribution to schools. It said the Danish aid agency is supposed to do that, but the Danes said it is the Education Ministry's responsibility.

Part of the slowness in moving books into the provinces is safety. The Afghan army must escort trucks of books into areas controlled by the Taliban, sometimes hiding the texts under sacks of rice or vegetables, said Eng Mohammad Zia of DANIDA, Denmark's aid agency.

Books also get stalled in provincial capitals because there is no coherent distribution plan or because money for transportation gets lost somewhere along the line, Danish and U.S. military consultants said.

The Mir Bacha Kot school finally received long-awaited high school textbooks over the winter break, but they are printed on flimsy newsprint and full of grammatical mistakes. Principal Meliha Haidar said she prefers to use earlier books, displaying one printed in 2004 and re-stapled, its beaten-up cover wrapped in plastic from a grocery bag.

Haidar said she has recruited foreign donors, put $100 of her own money into repairing benches, paid for gravel on the road leading up to the school and trained inexperienced teachers. What she can't do is generate quality textbooks, she said.

There are problems, too, even when books do make it to classrooms. Many are often printed on thin paper, glued instead of stitched, and full of errors, school officials said.

Asked about the quality mess, Nang, the education ministry's spokesman, said printers produced good-quality samples, then used lower-quality paper or binding on the actual books. Nang and many teachers said not all the books are of poor quality, but some are very bad.

Nang said donor countries send the money directly to the printers, so they are responsible for checking quality. But DANIDA, the U.S. military and the U.N. all say they count on the ministry for inspections, though the U.N. has just started following up with a review.

About 1 million of the books the ministry returned were from a batch contracted to a single print shop, an Afghan company called Baheer. Baheer's executive director, Shirbaz Kaminzada, said the donors and the Education Ministry told him to use lower-quality materials.

Once books come, the next problem is where to put them. Some texts have been ruined by rain and snow because schools had no storage space and kept them outside under a plastic tarp, said Zia, the DANIDA official.

Sometimes books take up classroom space.

"There are schools full of textbooks that can't be used for teaching because they're being used to store the textbooks," said Maj. Gary Jozens, a U.S. military liaison to the Education Ministry.

Despite all the complaints, teachers emphasize how happy they are to receive books at all. In the past, some said, there were only three books for a class of 30 or 40 students, so youngsters had to copy down the lesson.

Students are thirsty for education, the Education Ministry spokesman said.

"If the material is written on paper, or on animal skin, it doesn't matter, as long as it is provided," Nang said.

Associated Press writers Rahim Faiez and Amir Shah in Kabul and Noor Khan in Kandahar contributed to this report.