By JAMES RISEN

KABUL, Afghanistan — Eight years ago, Mahmoud Karzai was running a handful of modest restaurants in San Francisco, Boston and Baltimore. Today, Mr. Karzai, an immigrant waiter-turned-restaurant owner, is one of Afghanistan’s most prosperous businessmen.

The older brother of Hamid Karzai, the Afghan president, Mahmoud Karzai has major interests in the country’s only cement factory, its dominant bank, its most ambitious real estate development, its only Toyota distributorship and four coal mines.

BROTHERS KARZAI: The brothers include Ahmed Wali, accused of drug ties, and Hamid, now president, standing left and right center. Qayum, an ex-lawmaker, and Mahmoud, front at right, flank their father. (Photo: The New York Times)

He and a business partner run Afghanistan’s national Chamber of Commerce — which has far more clout than its American counterpart — allowing him to broker deals and lure foreign investors. For executives with problems with the Afghan government, he is the man to see. One prominent Afghan critic describes him as a “minister maker” with sway in hiring and firing top officials.

An unabashed advocate for money-making in the country his brother runs, Mr. Karzai attributes his success to having big ambitions and taking on ventures that others saw as too risky. “I’m investing in projects that require real work,” he said in an interview. “I’m in love with the idea that Afghanistan can become a Singapore, a Hong Kong.”

Mr. Karzai, though, clearly has exploited his connections, both in Washington and Kabul, to build his business empire. He has collected millions in American government loans for real estate developments in Kandahar and Kabul, capitalized on a friendship with Jack Kemp, the former Republican congressman, for introductions to American officials and international business executives, and benefited from what his rivals charge were sweetheart deals with the Afghan government.

Mr. Karzai’s swift rise has stirred resentment and suspicion among many Afghans, who have grown disaffected with the Karzai government and its seeming tolerance for insider dealing, favor trading, bribe taking and other unsavory activities. Rampant corruption fuels the Taliban insurgency, experts warn, and threatens American support for President Karzai, who is seeking re-election this year.

While Mahmoud Karzai has not been accused of any criminal wrongdoing, he has become a political liability, with critics complaining that his ascent was unfairly eased.

“If his brother wasn’t the president, would he have generated this much wealth, and gotten into this many deals?” asked Daoud Sultanzoy, a member of Parliament who has pushed for investigations into the Karzai family’s business activities. “One of the reasons the people don’t trust the government is because people in power have abused their power for personal gain.”

Humayun Hamidzada, President Karzai’s spokesman, denied that the president had shown favoritism to his brother. “The president does not allow anyone to use his name to get contracts or deals through him,” he said.

Mahmoud Karzai similarly dismissed complaints that he had traded on his family ties. “There is a great amount of jealousy and misinformation about me,” he said in an interview. “All the criticism that I’m getting insider deals because of my brother is flat-out wrong and lies.”

President Karzai has privately complained that Mahmoud Karzai’s business dealings are politically embarrassing, people who know him say, but he has not tried to rein in Mahmoud or his other siblings.

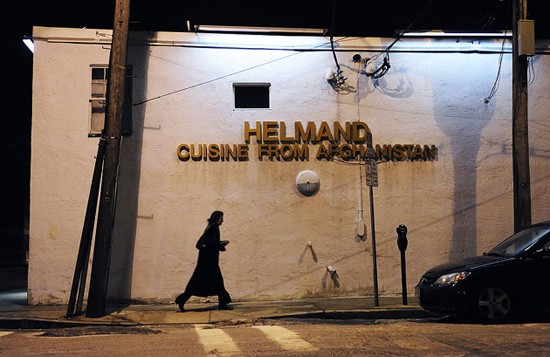

One brother, Qayum Karzai, who owns an Afghan restaurant in Baltimore, served until recently in the Afghan Parliament, though other members groused that he almost never showed up. He said in an interview that he is now an informal intermediary among President Karzai, Saudi Arabia and the Taliban.

Another brother, Ahmed Wali Karzai, the head of the Kandahar provincial council, has been accused of narcotics trafficking by Afghan and American officials, who are frustrated that the president has not taken action against him.

“President Karzai was seen initially as an honest man, but we don’t have a history of allowing the brothers of a leader to accumulate so much wealth,” said Saad Mohseni, the owner of an independent television station in Kabul. “His brothers are not allowing the president to think objectively about what is best for Afghanistan.”

An Eye for Opportunities

Mahmoud Karzai, an American citizen, kept his Maryland home, but travels back and forth to Kabul from a multimillion-dollar retreat in Dubai owned by his business partner. Back in his homeland, Mr. Karzai, 54, talks easily in Pashto to Kandahari businessmen in native dress and in fluent English to Westerners in suits. Politicians and business figures trade rumors and share gossip about him.. He says he is always looking for opportunities, while rivals fume that he has crowded them out or tries to get in on their deals.

“People in business would come to me and complain that Mahmoud always wanted a percentage of the new businesses,” recalled Zalmay Khalilzad, a former United States ambassador to Afghanistan. When he asked Mr. Karzai about such claims, he denied them, Mr. Khalilzad said in an interview.

Mr. Karzai said in the interview that he had chosen business projects that he said he believed would benefit Afghanistan. He insists that he has not gotten rich here because he has taken on so many liabilities. Though they provide no proof, many Afghan business and political figures describe him as one of their country’s wealthiest men.

To his critics, Mr. Karzai offers an unusual defense: Even if he wanted to, he could not use an insider’s advantage because his brother is ineffectual.

“He will never make a decision,” Mr. Karzai said of the president. “He will only talk politics. If you talk about the economy, he is not interested. He is not a problem solver.”

Mr. Karzai railed against government corruption and complained that his brother’s mismanagement of the economy made it difficult to make money. He said he had acted as a conduit for the business community because the bureaucracy was not responsive.

“People are looking for a channel of communications, so they say, ‘This guy is the president’s brother, he probably talks to his brother,’ ” Mr. Karzai said. “They get frustrated, and so they say, ‘Let’s go to the top.’ ”

Other business and political leaders scoff at his criticisms of the president, saying they are intended to disguise the tight ties between the brothers.

It is “100 percent an act,” said Gen. Hadi Khalid, who said he was fired from a top Interior Ministry post last year for opposing a deal involving Mahmoud Karzai’s business partner, Sher Khan Farnood.

American Support

Mr. Karzai moved quickly after the 2001 American-led invasion of Afghanistan to stake his claim in the postwar economy. In Maryland, he began brainstorming with other Afghan-American businessmen about how best to help restart the Afghan economy, just as the Bush administration was beginning to provide aid, business leaders said. He soon led a small group that set up a new Afghan Chamber of Commerce, winning $6 million from the United States Agency for International Development.

In an election last year, financed with more than $500,000 from the American aid agency, Mr. Karzai was chosen as the chamber’s vice chairman, and Mr. Farnood became chairman. Opponents charged that the voting was rigged to ensure that the two men came out on top, assertions that Mr. Karzai denies.

Mr. Karzai got other help from Washington, thanks to prominent friends. He made a point after the Sept. 11 attacks of getting to know conservative Republicans, including Mr. Kemp. In an interview, Mr. Kemp said he introduced Mr. Karzai to officials at the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, a federal agency that provides financing to American businesses abroad.

Mr. Kemp said he wanted to encourage investment in Afghanistan, adding that he had not benefited from Mr. Karzai’s deals. “I imagine he has dropped my name around Kabul and Kandahar, but I can assure you I have no equity or interest in his businesses,” he said.

According to OPIC officials, two companies tied to Mr. Karzai got loans of more than $5 million to finance his Kandahar real estate development and a large apartment complex in Kabul.

The Kandahar venture, an ambitious plan to build a residential community that Mr. Karzai named Aynomina (“a place to live”) — quickly stirred an outcry. The 10,000-acre property in the city of Kandahar was owned by the Afghan Army, but Kandahar officials turned it over to Mr. Karzai virtually free.

Mr. Karzai said the city officials wanted him to take the land so powerful warlords could not seize it. The Kandahar governor, he said, agreed that his government would be paid for each lot only when Mr. Karzai’s development firm sold a home built on it.

But no deal was worked out with the army. In 2005, Afghan troops stormed the construction site, shooting wildly. Brig. Gen. Shahtory Habibullah, who oversees properties for the Ministry of Defense, said Mr. Karzai’s company had never paid the army anything. The dispute still simmers.

“The land mafia has taken my land,” the general said in an interview. “When I go to the property, I cry for it.”

Mr. Karzai said he had built more than 200 homes, with 60 or so under construction, that had proved popular with the emerging Afghan middle class. “We have three-bedroom models selling for $20,000, “ he said. “That house — we cannot keep up with.”

A Big Cash Deal

Mr. Karzai took on his biggest venture when he and other investors assumed control of Afghanistan’s only cement factory. Operating rights for the plant were put up for auction by the Ministry of Mines, and Mr. Karzai and his partners won when they were the only bidders to show up with $25 million in cash. Mr. Karzai said the auction rules required that. But Mr. Sultanzoy, the member of Parliament, charges that the cash requirement was a last-minute provision devised to benefit Mr. Karzai.

“They brought the cash and put it on a table in front of the minister and then took it away,” Mr. Sultanzoy said.

The group did not have to make an up-front payment. Instead, it pays rent and shares royalties with the government, Mr. Karzai said.

He has had access to the financing required for his projects through the Kabul Bank, the largest commercial bank in Afghanistan, where he sits on the board. Mr. Farnood, the bank’s founder, helped Mr. Karzai become an investor by issuing him a loan to buy shares in the bank, Mr. Karzai said.

He is also the majority owner of the only Toyota distributorship for Afghanistan, thanks in part to Mr. Kemp, who has served on Toyota’s United States diversity advisory board and introduced Mr. Karzai to the automaker’s executives.

Mr. Khalilzad, who denied speculation that he planned to challenge President Karzai in the coming election, recalled that the president once confided that he was angry about the Toyota deal and wondered aloud whether he should try to block it. He said he believed that the president spoke to the Japanese ambassador on the issue, but to no avail.

Ashraf Ghani, a former Afghan finance minister who has been considering running for president this year, said that when President Karzai asked him to join his government, he was concerned about the potential for insider dealing by the Karzai family.

“Is this going to be a family enterprise?” Mr. Ghani recalled asking. “He said absolutely not. But that is what it has become.”

Barclay Walsh contributed research from Washington.