By Jean MacKenzie in Kabul

International pressure is all that stands between a young journalism student and the death penalty, say his supporters.

A subdued, anxious crowd filled the courtroom of the Kabul Appeal Court on June 15 for the latest installment in the case of Sayed Parwez Kambakhsh, the Afghan journalism student facing a death sentence for blasphemy.

There was little evidence of the international media in the courtroom, and the few foreign diplomats present sat quietly, some conferring with the defence from time to time.

The lack of a strong international presence could be bad news for Kambakhsh. Several sources close to the case have said international attention is the only thing sustaining his appeal.

“If the eyes of the world were not on him, this judge would just hang Kambakhsh,” said one insider, speaking on condition of anonymity.

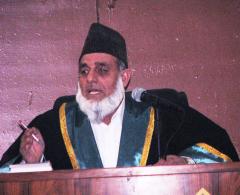

Presiding judge Abdul Salam Qazizada has weathered several Afghan administrations. He is a holdover from the Taliban regime, and his antagonism to the defendant was visible.

By the end of the June 15 session, it was clear there was to be no swift end to proceedings against Kambakhsh, 23, who is accused of “insulting Islam and abusing the Holy Prophet Mohammad”.

For the fourth time in the past 30 days, the case was adjourned without a decision.

During the session, Qazizada appeared to take on the role of prosecutor rather than impartial judge, engaging in a legal duel with defence attorney Mohammad Afzal Nooristani. Lacking a gavel, he repeatedly banged his pen against his microphone in an effort to halt Nooristani’s defence of his client.

Time and again the judge attacked Kambakhsh, who sat pale but composed in the defendant’s chair.

“Just tell me why you did these things,” insisted Qazizada. “What were your motives?”

“I cannot give you reasons, since I did not do anything,” responded Kambakhsh.

The young student is accused of downloading and distributing a text from the internet that criticises, sometimes quite harshly, Islam’s treatment of women. The prosecution contends that Kambakhsh added several paragraphs of his own, and that this proves he is “against Islam”.

In Afghanistan, this is a capital crime, at least according to the court in Balkh province which issued the death sentence in a closed session in late January.

Kambakhsh has consistently denied downloading or handing out the article, still less writing any part of the offending text.

He claims that a confession he signed while held in custody by the National Security Directorate was coerced, and stated that security forces broke his nose and left hand. He told the court that he came under psychological pressure and signed the confession out of fear.

A previous session, on June 1, ended with a defence motion to have Kambakhsh examined for signs of physical trauma.

The results from the department of forensic medicine were inconclusive. In findings read out on June 15, doctors stated that while Kambakhsh’s nose showed a slight deviation, it could be a congenital defect as well as evidence of injury. No pathology was found in the left hand, but, according to the statement, there had been ample time for any injury to heal in the seven months since the beating was alleged to have taken place.

This session was the first time the defence had been allowed to read out a statement rebutting the charges against Kambakhsh.

KBAUL, Jan 31: Members of Afghanistan Solidarity Party conduct a protecting demo, considering the death sentence illegal which is handed down by a court to a young journalist Sayed Parviz Kambakhsh accused of blasphemy. PAJHWOK/Ahmadullah Salemi

The prosecution also gave a statement, outlining the evidence that had been gathered.

Once prosecutor Ahmad Khan Ayar concluded his statement, he traded a few jabs with Nooristani, but was soon overshadowed by the presiding judge.

“It is clear that this text belongs to you,” Qazizada told Kambakhsh, When the defendant attempted to protest, he was silenced by the judge’s irritable banging on the mike.

After lunch, the case took an even more sombre tone, as Qazizada intensified his pressure on the defence.

“Kambakhsh may have wanted to make himself popular by writing this text,” he thundered, his voice in the microphone nearly drowning out the simultaneous translation.

“Why was he the only one arrested? Balkh University is very large – why should Sayed Parwez Kambakhsh be arrested and prosecuted? Can you tell me?” he asked, turning to the defendant.

Kambakhsh tried to explain once again that he had no connection with the offending text, that he had no idea why he was arrested, and that he had made the confession under duress.

But the judge was not convinced.

“I have seen the documents, I have read them,” he roared. “[The content] is against Islam.”

The court was also presented with a long list of Kambakhsh’s alleged failings, such as that he was a socialist, impolite, and asked too many questions in class. He was also accused of having swapped off-colour jokes with friends via text messaging on his mobile phone.

When the judge read out one text-message anecdote in a tone of high indignation, several people in the audience had to repress a smile.

The court finally adjourned in order to summon witnesses from Balkh province, whose written testimony provided the body of the case. No date has been set for the next session.

The judge, Abdul Salam Qazizada is a holdover from the Taliban regime, and his antagonism to the defendant was visible.

The defendant’s brother, Sayed Yaqub Ibrahimi, who has been a reporter with IWPR for the past six years, was visibly upset by the day’s events.

“Welcome to the Middle Ages,” he grimaced.

A foreign diplomat also expressed consternation at the way the trial was being conducted.

“I do not see any way out,” said the diplomat, speaking on condition of anonmity.

The government of Afghanistan has come under high-level pressure to find a solution for Kambakhsh, whose case has come up in talks between President Hamed Karzai and several international leaders, including United States Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and British Foreign Secretary David Miliband.

Karzai has made public assurances that “justice will be done” but so far has not openly intervened in the case.

In the months since his sentencing, Kambakhsh has become an international figure, his face appearing on posters and the front pages of newspapers. Britian’s Independent newspaper launched a campaign, gathering tens of thousands of signatures to support the young man.

There is a danger that as time drags on, the level of interest will drop, along with the protection it affords.

“Time means nothing to us,” said Qazizada, adjourning the case yet again.

“That is easy for him to say,” said Ibrahimi, as his brother was led out of the court in handcuffs. “He goes home every night. Parwez is spending his time in prison.”