Rosie DiManno

In the past 20 months, Attorney General Abdul Jabar Sabet has arrested some 300 top-echelon Afghan officials and charged them with corruption.

"Ask me how many of them are in jail."

How many of them are in jail?

"Not one."

There is the chronic malady of Afghanistan in a nutshell. Justice is a mug's game, the rule of law more useless than the paper it's written on.

Not a single authority in the nation, right up into the president's office, has the clout to oppose a powerful alignment of forces that are a law unto themselves: Warlords, ministers, parliamentarians, the military, police, tribal elders and wealthy entrepreneurs who are making a killing in the free-for-all of multi-billion-dollar international aid, a tsunami of cash that has made tycoons out of two-bit larcenists and filchers.

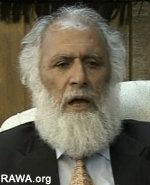

"It is very frustrating," sighs Sabet, running long fingers through a cascading white beard, shaking his leonine head.

He looks like Moses, but his word is not quite law in these parts.

"In theory, I have the power to arrest anyone in this country if he's involved in corruption. But in practice, there are some people who are above the law, unfortunately, and I cannot bring them to justice.

"I call them The Untouchables."

They are in the central government, the provincial governments, the district centres, police stations, army garrisons, the banks, the aid agencies – not a sector of Afghan society is without contamination of corruption.

Even, Sabet admits with a wince, inside his own department.

"I have not even been able to clean my own house," he told the Star in an astonishingly frank interview this week.

"We have a lot of dirty, dishonest prosecutors."

He has lived in Montreal – a wife and three grown children still reside there – spending years in the comparative law department of McGill University before being tapped by the United Nations for a post in post-Taliban Afghanistan. President Hamid Karzai appointed him attorney general just under two years ago.

There are some – in the diplomatic community and the media – who have pointed an accusatory finger at Sabet himself.

Last month, during his formal "accountability to the people program" session – a kind of public performance report card – Sabet burst into tears when a journalist inquired about the posh mansion he's building in Kabul's most deluxe neighbourhood, an enclave he'll share with some of Afghanistan's richest drug kingpins.

Sabet – believed by some to covet the presidency – never really did provide an answer, launching into an oration about his office's inability to arrest the super-powerful violators of Afghan law.

The most notorious case involves Gen. Abdul Rashid Dostum, who flagrantly ignored a warrant issued for his arrest after the Uzbek warlord allegedly attacked a rival – head of the Afghan Turk Association – in his Kabul home recently, beating him so badly that the man was hospitalized.

"At least I was able to suspend him from his job," Sabet told the Star, meekly. "So I have been successful ... a little bit."

Dostum had been chief of staff to the Afghan army commander, a symbolic position.

At the accountability session, 63-year-old Sabet spoke of corruption in a number of ministries, claiming those ministers had secured release of the accused.

He vilified the governors of several provinces for corruption and embezzlement, heaping abuse particularly on the governor of Nangarhar province, an Ultra-Untouchable who Sabet says has misappropriated about $6 million intended for reconstruction projects.

Among those Sabet charged in the last year were deputy governors, chief provincial financial officials, judges, and "a good number of police generals."

All of them waltzed, either buying their way out of jail or using influential friends and tribal affiliations to secure unfettered release.

"It makes me crazy," Sabet mumbles.

Venal parliamentarians are even greasier to the touch, utterly beyond his reach. "Parliamentarians are protected by the constitution."

The system demands that before a parliamentarian can even be charged, the prosecutor must send a letter detailing the allegation to the minister of parliamentarian affairs.

He vilified the governors of several provinces for corruption and embezzlement, heaping abuse particularly on the governor of Nangarhar province, an Ultra-Untouchable who Sabet says has misappropriated about $6 million intended for reconstruction projects.

Among those Sabet charged in the last year were deputy governors, chief provincial financial officials, judges, and "a good number of police generals."

That minister then informs the appropriate house – lower or upper – which in turn votes on whether to proceed with an investigation. "But so far that has never happened."

So Sabet takes his triumphs from the "smaller fish" that have been nabbed and convicted in trials held behind closed doors. Few are allowed to witness the incompetence of jurisprudence as practised in Afghanistan.

This, says Sabet, is his primary focus – elevating the quality of prosecutors and judges.

He has about 2,800 prosecutors around the country but few of them have any real legal training, especially in the provinces. In Khost, for instance, out of 74 prosecutors, only four are genuine lawyers, the rest just laymen.

"We had war in this country for 30 years. Educated prosecutors were either forced to leave or they retired. Now, we do not have many educated people to work as prosecutors."

At the Rome conference on the rule of law in Afghanistan a year ago, Afghanistan was promised funding specifically for this purpose.

It hasn't materialized. Italy, which was given the task of working with the justice sector, has taken precisely one candidate – Sabet's own secretary – for legal training in Rome.

Ideally, Sabet would like to implement a three-pronged justice-training program. Long-term: Sending as many prospects to Western universities for solid legal training. Mid-term: A one-year intensive course in Kabul for newly graduated lawyers. Short-term: A two-month crash course for non-lawyer prosecutors from the provinces, "so they can at least learn the basics of law, investigation, collecting evidence."

RAWA: Jabar Sabet, Afghanistan's attorney-general is a dark-minded person who has been a member of the Gulbuddin Hekmatyar terrorist band in the past.

So far, there isn't the money for any of that.

"The international community makes a lot of promises. But nobody has come up with anything real."

The Americans, however, have indicated they will airlift "some" bright lawyer candidates to the U.S. for training, soon.

They also pay the $27,000 monthly rent on the attorney general's building where Sabet takes petitions from the public three days a week.

In the meantime, Sabet will continue trying to weed out the worst offenders from his own legion of corrupt prosecutors.

"We have corruption in all our law enforcement agencies – police, judges, prosecutors. Now, I would not use this as an excuse for their behaviour, but my prosecutors make only $60 a month.

"That's less than you would pay for a week's parking in Toronto."