In northern Afghanistan it appears some parents are being driven by poverty and hunger to marry off their daughters at an early age. Jenny Cuffe investigates for Radio 4's Seven Days.

Farida (not her real name) was paid 40,000 Afghani (£400) last summer for marrying her 13-year-old daughter to her father's 20-year-old cousin.

The child, her freckled face half hidden behind a blue veil, says she does not like her husband, and begins to cry.

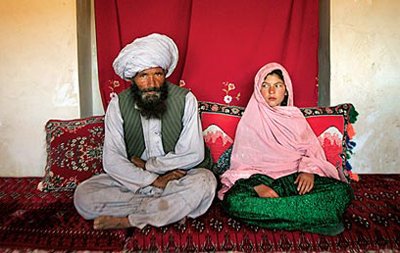

This sobering image, showing a 40-year-old groom sitting beside his 11-year-old future bride in Afghanistan, brought Stephanie Sinclair top honors in the annual Photo of the Year contest sponsored by the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF).

"I didn't want to marry, it was my parents' decision," she said. "I dreamed I would be able to finish my education. I had no choice."

Asked why she is making her daughter unhappy, Farida replies simply: "It is her life, it is her fate."

Badakhshan's independent MP Fauzia Kofi says she has seen an increasing number of such child brides in the last two years.

"I don't call it marriage, I call it selling children," she says.

"A nine or 10-year-old - you give her away for wheat and two cows."

High prices

The cause of the trend, according to Fauzia Kofi, is poverty.

Farida and her daughter live in the village of Wandian, high in the mountains of Badakhshan and a fortnight's journey by donkey from the nearest big town, Faizabad.

Badakhshan deputy governor Dr Mohammed Zarif reports 60 deaths from cold and hunger and the loss of 7,000 livestock over the five months that the district has been cut off from the rest of the world by snow.

Meanwhile, some food in the local market has doubled in price in the last year - a result both of Badakhshan's inaccessibility, and of global food shortages.

The British aid agency, Oxfam, has brought them vegetable seeds and fertiliser, but villagers in Wandian say their oxen have died and they need a plough.

Fauzia Kofi believes child marriages will only end if Badakhshan gets investment to reduce poverty, and more help to improve the food supply.

A midwife in the village of Khordakhan, Hanufa Mah, agrees that alleviating poverty is key.

She says she tries to teach parents not to marry their girls too young but some feel they have no choice.

One girl she helped through labour was only 10 years old.

"The girl was so small. I held her in my lap until the child was born," she says.

UN figures show that more women die in childbirth in Badakhshan than anywhere else in the world, and mothers under the age of 15 are most at risk.

No quick fix

Afghanistan's finance minister Anwar al-haq Ahadi does not, however, expect regions such as Badakhshan to be lifted out of poverty quickly.

"I'm afraid it's going to take quite a while... what we're trying to do now is just the very basics.

"Right now we are the fourth or fifth poorest country in the world.

"We hope we will move in ranking by another two or three steps, but still, Afghanistan in five years from now will be a very poor country."

The outlook for girls in Afghanistan's remote villages appears bleak then, especially if global food shortages continue.

Their hopes of education are likely to be frustrated, and they will continue to face the hazards of early pregnancy.