Rekha Basu

As the young Afghan woman saw it, she had three choices in the face of the repression and violence that had killed both of her parents and turned her country into a chess game between superpowers and fundamentalists.

She could flee to America to live with relatives. She could commit suicide, as so many other despondent young Afghans were doing. Or she could do what she did and take what she calls "the way of struggle," by joining the resistance.

Resistance had been the path of her mother, an activist with the underground Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan (RAWA), who was assassinated when Zoya was 14. That's the organization Zoya joined.

Now 28, she goes by a pseudonym because she's a target of extremists. She was in Des Moines this week appealing for what some Americans might find surprising, given her opposition to the terrorists: an end to the U.S. occupation and war.

The U.S. government has claimed credit for ousting the Taliban and liberating Afghanistan's people. But after eight years of growing violence on all sides, and with the Taliban still in control of 80 percent of the county, Zoya says it's time for us to leave. In Wednesday's column I discussed some of her views. But her own story and the history it illuminates deserve a separate telling.

Born as the Soviets were coming to power in Afghanistan, she has known only occupation of some form her whole life. After her parents' deaths, she moved to Pakistan with a grandmother, where she was educated in a RAWA school, and studied law.

For all the fight and fearlessness in her, she is still a motherless child with a vulnerability that makes you want to hug her or give her cough drops, as my colleague Linda did, after hearing she had a cold.

The word "revolutionary" conjures up images of armed warfare but RAWA is a pacifist organization doing political and social work. Founded in 1977 to give voice to women, it now claims 2,000 members. Early on, it campaigned against the Russian forces and Russian-backed government. But many Afghans feel the U.S. turned its back on Afghanistan after the fall of the Soviet Union left a void into which the Taliban, and other fundamentalist groups we had supported, stepped.

"We saw floggings and stonings to death," recounted Zoya. "The doors of schools were called gateways to hell, and computers were called devil boxes." The first image smuggled out of Afghanistan of Taliban leaders executing a woman in a public stadium were taken by RAWA members with a hidden video camera. Members have turned their burkhas - imposed by the Taliban to keep them covered head to toe - into advantages.

RAWA is funded by donors, international non-governmental organizations and homespun businesses run by members. It operates schools, orphanages and mobile health units. And it offers an inspiring counterpart to the impression of Afghan women as silenced and immobilized.

The 2001 U.S. invasion, in pursuit of Osama bin Laden, routed Taliban from the capital city of Kabul, but some 34 provinces remain under Taliban rule.

Occupying governments may have their strategic long-term interests. But Zoya's appeal is to the American people.

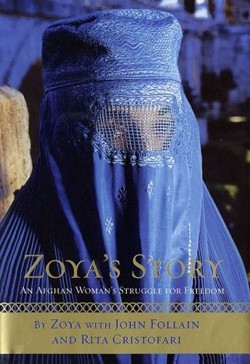

I've met many interesting people on this job, but seldom has a subject moved me as Zoya did in her direct, smart, unassuming way. She isn't seeking personal glory. When book authors John Follain and Rita Cristofari asked to tell her story, she balked. The struggle wasn't about her, she insisted. But she collaborated with "Zoya's Story: An Afghan Woman's Struggle for Freedom" (HarperCollins, 2003) to help promote the cause.

This struggle is, of course, much bigger than one person. But seeing it through the lens of this one makes it both personal and poignant and gives it particular urgency.